| New York

Architecture Images- notes |

|

30 under 30 The Watch List of Future Landmarks |

| The 30 most significant

buildings under 30 years old (the age needed for landmark status in New

York). |

| |

|

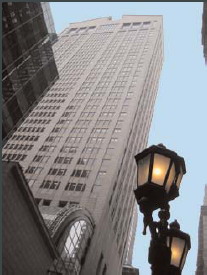

1.

Isamu Noguchi Garden

Museum

Isamu Noguchi and

Shoji Sadao

1985

32-37 Vernon Boulevard

Queens

www.philip.greenspun.com |

|

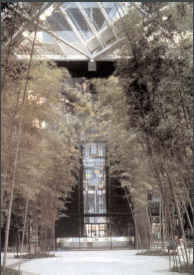

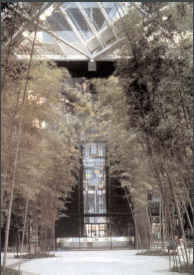

2.

New York Public Library

South Court

Davis Brody Bond LLP

2002

Fifth Avenue at 42nd Street

© Peter Aaron/ESTO |

|

3.

IBM Building

Edward Larrabee Barnes

Associates

1983

590 Madison Avenue |

|

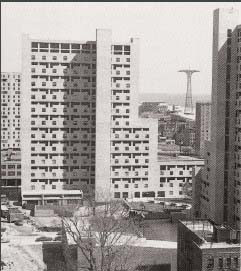

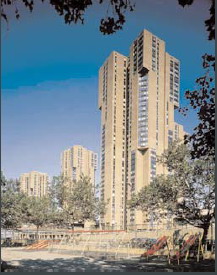

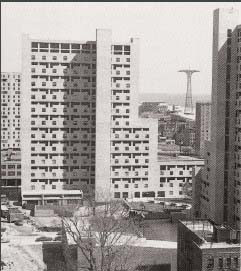

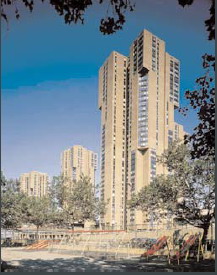

4.

Tracey Towers

Paul Rudolph with

Jerald L. Karlan

1974

20, 40 West Mosholu

Parkway

Bronx |

|

5.

LVMH Tower

Christian de Portzamparc

& Hillier Architecture

1999

19 East 57th Street |

|

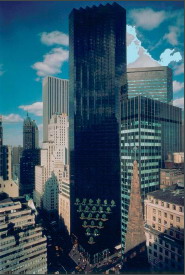

6.

Trump Tower

Der Scutt with Swanke

Hayden Connell Architects

1983

725 Fifth Avenue

|

|

7.

Storefront for Art and

Architecture

Steven Holl

1993

97 Kenmare Street |

|

8.

Sea Park East Apartments

Hoberman & Wasserman

1975

Surf Avenue at

West 27th Street

Brooklyn

|

|

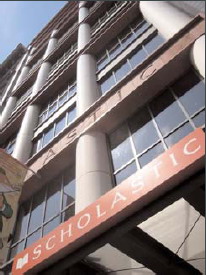

9.

Scholastic Building

Aldo Rossi with Gensler

2001

557 Broadway |

|

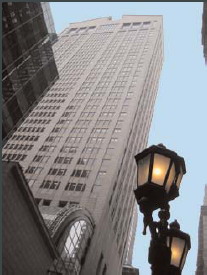

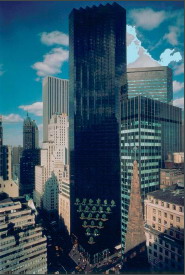

10.

AT&T/Sony Building

Philip Johnson/John Burgee

1984

550 Madison Avenue

|

|

11.

The New 42nd Street

Studios

Platt Byard Dovell

Architects

2000

229 West 42nd Street |

|

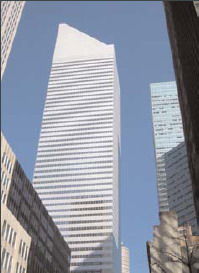

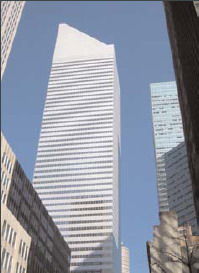

12.

Citicorp Center

Hugh Stubbins &

Associates/Emery Roth &

Sons

1977

153 East 53rd Street

|

|

13.

Woodhull Medical and

Mental Health Center

Kallmann McKinnell & Wood

Architects, Inc.

1977

760 Broadway at

Flushing Avenue

Brooklyn |

|

14.

Roosevelt Island

Tram Station

Prentice & Chan, Ohlhausen

1976

Second Avenue at

59th Street

|

|

15.

173/176 Perry Street

Condominium Towers

(detail)

Richard Meier

2002

173/176 Perry Street |

|

16.

Taino Towers

Silverman & Cika

1972-1979

221 East 122nd Street

|

|

17.

Alfred Lerner Hall

Bernard Tschumi/

Gruzen Samton

1999

2920 Broadway |

|

18.

Korean Presbyterian

Church of New York

Greg Lynn FORM,

Garofalo Architects and

Michael McInturf Architects

1999

43-05 37th Avenue

Queens |

|

19.

Eastwood

Sert, Jackson & Associates

1976

510-580 Main Street

Roosevelt Island |

|

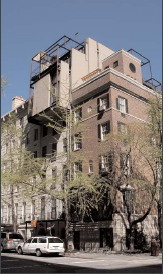

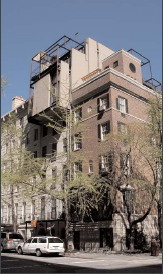

20.

Paul Rudolph Penthouse

Paul Rudolph

1977-83

23 Beekman Place

|

|

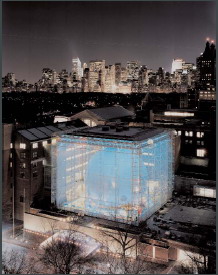

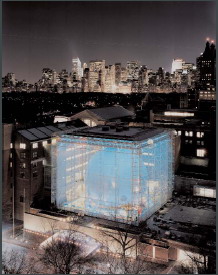

21.

AMNH Rose Center for

Earth and Space

Polshek Partnership

Architects

2000

Central Park West at

81st Street |

|

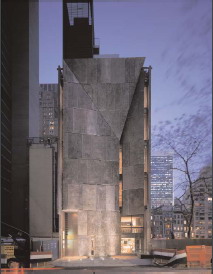

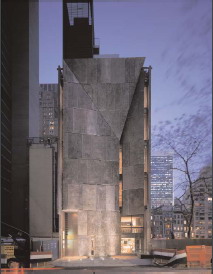

22.

Austrian Cultural Forum

Raimund Abraham

2002

11 East 52nd Street

|

|

23.

Grace Building

and 9 West 57th Street

Skidmore, Owings &

Merrill LLP

1974

1114 Sixth Avenue |

|

24.

Takashimaya

John Burgee Architects

1993

693 Fifth Avenue

|

|

25.

American Folk Art Museum

Tod Williams Billie Tsien

Architects LLP

2001

45 West 53rd Street |

|

26.

Firehouse for Engine Co.

233 & Ladder Co. 176

Eisenman Robertson

Architects

1985

25 Rockaway Avenue

Brooklyn

|

|

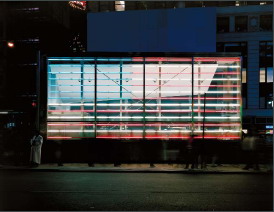

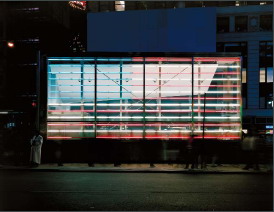

27.

U.S. Armed Forces

Recruiting Station

Architecture Research

Office LLP (ARO)

1999

Times Square |

|

28.

New York Times Printing

Plant

Polshek Partnership

Architects

1997

26-50 Whitestone

Expressway

Queens

|

|

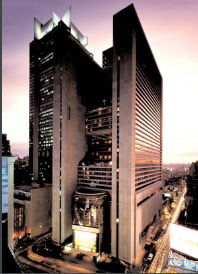

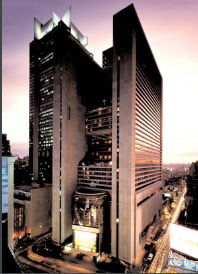

29.

New York Marriott Marquis

Hotel

John C. Portman, Jr.

1981-1985

1531-1549 Broadway |

|

30.

9 West 57th Street

and Grace Building

Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

LLP

1974

9 West 57th Street

|

|

31.

Waterside Plaza

Davis Brody & Associates

1974

FDR Drive at 25th Street |

30 Under 30: The

Watch List of Future Landmarks

When, many years from now, we look back at the close of the 20th century,

which buildings will we select to tell our story?

An independent jury appointed by the Municipal Art Society of New York has

just released a list of 30 contemporary buildings that it believes to be

potential future landmarks. 30 Under 30: The Watch List of Future Landmarks

includes residential, cultural, religious and industrial buildings

constructed between 1974 and 2004 (photos). The list begins chronologically

with Skidmore, Owings & Merrill's Grace Building and its sibling 9 West 57th

Street, completed in 1974; and ends with Richard Meier's 173/176 Perry

Street Condominium Towers, completed in 2002. Spearheaded by the Society's

Kress Fellow for Historic Preservation, Vicki Weiner, work on the Watch List

of Future Landmarks began shortly after Mr. Meier's 1977 Bronx Developmental

Center disappeared under a radical alteration in 2002. Despite an

international reputation as a late Modern masterpiece, the building was not

yet 30 years old and therefore ineligible for landmark status and

protection. The loss of the building served as a wake-up call for the

Society to monitor -- watch -- these buildings today so they will survive

long enough to help tell the story of the late 20th century.

Over 150 buildings were nominated to the Watch List by design

professionals and the public. The jury used a set of established criteria to

judge the buildings based on their artistic, technological, historical and

canonic merits, and weighed the influence they had on design and culture in

the city and worldwide. Sherida Paulsen, an architect who was chairman of

the Landmarks Preservation Commission from 2001 to 2003, chaired the jury,

which included: Paola Antonelli, a curator at the Department of Architecture

and Design, MoMA; New York magazine architecture critic Joseph Giovannini;

interior designer Kitty Hawks; Paul Makovsky, senior editor of Metropolis

Magazine; architect Greg Pasquarelli of the firm SHoP; architectural

historian Nina Rappaport; David Sokol, managing editor of I.D. Magazine; and

Jacob Tilove, architectural historian at Robert A.M. Stern Architects.

http://www.mas.org/ContentLibrary/30Under30.pdf

http://www.mas.org/ContentLibrary/30Under30photos.pdf

|

| THE MUNICIPAL ART SOCIETY I

457 MADISON AVENUE I NEW YORK, NY 10022 I (212) 935-3960 I

WWW.MAS.ORG

In Preservation Wars, a Focus on

Midcentury

By ROBIN POGREBIN

Published: March 24, 2005

Arguing that significant buildings are not getting their due, advocates of

midcentury architecture are stepping up pressure on the city's Landmarks

Preservation Commission to hold full public hearings on proposals to

raze two movie theaters on the Upper East Side of Manhattan.

Plans have been announced to convert Cinemas 1, 2 & 3, a 1962

International-style theater on Third Avenue across from Bloomingdale's,

into retail space. The Beekman, a 1952 late Streamline Moderne design at

Second Avenue and 66th Street, is to be replaced by a breast and

diagnostic imaging center run by Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

The theater is scheduled to be closed down this summer.

On another front, a lawsuit was filed against the city last week in New

York State Supreme Court seeking to prevent reconstruction of 2 Columbus

Circle into the Museum of Arts and Design. The marble-clad building with

a "lollipop"-motif facade by Edward Durell Stone once housed Huntington

Hartford's Gallery of Modern Art. The landmarks commission has never

held a public hearing on the future of the building, on which demolition

is expected to begin in late May.

These two different battlefronts represent a larger argument on the part

of preservationists that the commission has generally neglected postwar

architecture and been unresponsive to their concerns about Modernist

sites.

"The commission ought to hear the arguments and let them be debated in a

public forum - that's democracy," the architect Robert A. M. Stern, who

is active in preservation issues, said in an interview.

But Holly Hotchner, director of the museum going into 2 Columbus Circle,

said, "There are no landmarks hearings on many buildings."

Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts, a group that is

spearheading opposition to the alteration of the movie theaters, said in

a statement: "These insensitive and destructive actions highlight the

urgent need to protect the Modern architecture on the Upper East Side

and across the city. The Landmarks Preservation Commission has

designated some important Modern buildings, but most remain at risk."

John Jurayj, co-chairman of the Modern Architecture Working Group, an

advocacy organization, said at a commission hearing last week on the

Jamaica Savings Bank in Queens, itself an example of mid-20th-century

architecture: "Modern preservation is in a major crisis in our city, a

crisis that is shortly going to get worse unless the Landmarks

Preservation Commission starts to act more aggressively."

At the same meeting, Kate Wood, the executive director of Landmark West, a

community group focused on preservation on the Upper West Side, reproved

the commission for not putting the fate of 2 Columbus Circle before the

public. "If the Landmarks Commission held a public hearing for 2

Columbus Circle, literally hundreds of people would attend and testify -

both for and against designation," she said. "The question is, what more

will it take?"

Diane Jackier, a spokeswoman for the commission, said: "All of the

preservation advocacy groups say the commission is slow to respond. The

commission balances the concerns of advocacy groups across the city with

our own interests."

Robert B. Tierney, the commission's chairman, was traveling out of the

country this week and unavailable for comment, Ms. Jackier said.

To be sure, the commission's work has been hampered in part by a low

annual budget - $3.5 million - and staff cuts over the past decade. The

Modern Architecture Working Group acknowledges these handicaps but has

urged the commission to step up designations of sites as landmarks. Last

year, the commission designated 12 individual landmarks and 3 historic

districts, which Ms. Jackier said amounted to a total of 220 buildings,

compared with 25 individual landmarks and 2 districts amounting to 261

buildings in 2000.

The group has also asked the commission not to give building owners too

much advance notice of hearings on their landmarks. Otherwise, the

preservationists argue, owners may pre-emptively alter the buildings.

Preservationists had repeatedly asked for hearings on the 1961 Summit

Hotel on Lexington Avenue and the 1949 Paterson Silks Building at Union

Square, both designed by the Miami architect Morris Lapidus. Hearings

were finally scheduled, but not until demolition had begun on the Silks

Building.

The fight over 2 Columbus Circle has intensified since the city agreed to

sell the nine-story building to the Museum of Arts and Design in June

2002, for $17 million. The museum, now on West 53rd Street, plans to

reconstruct it for about $30 million according to a design by Brad

Cloepfil of Allied Works Architecture. Construction is expected to begin

by the middle of this year and to be completed in mid-2007.

Some call 2 Columbus Circle ugly and say they would just as soon see it

go. But many Modernists argue that the 1964 building is an important

example of postwar architecture. "It is a building that should be saved;

it's still not too late," said Mr. Stern, the architect. "Under any

definition of what a landmark is - culturally, physically and

geographically - this is a landmark."

The lawsuit filed last week was brought by property owners in the Parc

Vendome Condominiums near Columbus Circle and by Landmark West. It aims

to block the sale on the grounds that it was conducted without due

process in violation of the New York State Constitution, the New York

City Charter, the General Municipal Law and New York's public trust

doctrine.

Ms. Hotchner said in an interview yesterday that the lawsuit "in no way

affects our interest in going forward" with the museum and called it "an

example of abuse of the legal system to subvert the public process."

Preservationists opposed to the building's renovation have already been to

court on the project. Supported by the National Trust for Historic

Preservation, the plaintiffs challenged the environmental review of the

project and the failure by the landmarks commission to hold a public

hearing on it.

In February, a five-judge panel of the Appellate Division of State Supreme

Court unanimously upheld an earlier dismissal of that lawsuit.

Landmark West argues that its recent lawsuit would not have been necessary

had the landmarks commission held a hearing as requested. "It's because

they've refused to deal with this that we've had to resort to the

courts," said Ms. Wood of Landmark West.

The commission's designation committee has said that no public hearing was

ever held because it determined in 1996 that landmark status was not

warranted for 2 Columbus Circle.

But several people who work in architecture or preservation have continued

to appeal for a hearing, arguing that the commission was wrong to shut

off public debate.

Last October, in testimony before the City Council subcommittee

responsible for landmark preservation, Beverly Moss Spatt, a former

chairwoman of the commission, described the commission as "totally

isolated and in total disregard for public opinions."

Anthony M. Tung, a former member of the commission, told the subcommittee

that the public was "being barred in numerous improper ways from a

process which the council in its wisdom designed to be open and

participatory."

In November, a coalition of civic organizations produced a report,

"Problems Experienced by Community Groups Working With the Landmarks

Preservation Commission," that detailed their complaints and suggested

areas for change.

Friends of the Upper East Side describes Cinemas 1, 2 & 3 as the first

"piggyback" duplex movie theater in the United States - "a significant

milestone in the development of movie theater design."

The group cited the glass corner on East 66th Street and the ribbon

windows on East 65th Street as examples of the International-style

design "enlivened with a tilted glass facade and sloping streamlined

lounge ceiling that refers stylistically back to the Moderne style of

the 1930's."

But it also noted that the theater had already undergone extensive

alterations of its exterior, including the replacement of Venetian tiles

with a white stucco wall. In addition, the Upper East Side group says,

important artworks in the interior have been removed, including an

abstract oil painting by the Russian-born artist Ilya Bolotowsky, a

geometric mural by Sewell Sillman and copper leaf-shaped chandeliers

from Denmark.

Friends of the Upper East Side says the theaters are two of the few

remaining art film houses in Manhattan. "We've lost almost all of them,"

said Seri Worden, the group's executive director.

Mr. Stern, the architect, said the issue was not merely the theaters'

architectural value, but their contribution to the neighborhood's

character. "They provide a layer of the past in relation to new things,"

he said.

|

|

How the Spirit of Ayn Rand Haunts

the City

BY Julia Vitullo-Martin

March 24, 2005

http://www.nysun.com/article/11079

Ayn Rand's spirit seems to be returning to haunt us all, infusing

downright bizarre criteria into today's increasingly heated debate over

preserving modernist buildings. The preservationists, naturally enough,

want to protect everything designed by the Howard Roark-style,

celebrated modernist architects who argued they were erecting pure

buildings in a compromising world. Buildings by original Bauhaus

architects like Joseph Urban are on everyone's list, as are most

buildings by Yale brutalist, Paul Rudolph.

But the preservationists are also lobbying to landmark buildings by the

real life equivalents of Roark's protagonist, Peter Keating, whose

mediocrity was rewarded by major design contracts while Roark was

expelled from New York. Buildings by Philip Johnson, for example, often

thought to be the model for Keating, are now showing up on most

preservationist lists, even though almost no one would claim these

buildings are illustrious. Since landmarking has the effect of

rigidifying current use and preventing evolutionary change, New Yorkers

need to pay close attention to this debate.

The Municipal Art Society's watch list of 30 Under 30 includes, for

example, the egregious Marriott Marquis Hotel designed by John Portman,

the immense IBM Building designed by Edward Larrabee Barnes, and Philip

Johnson's cathedral-size AT&T/Sony Building. Do New Yorkers really want

these structures pre-empting all future uses? Are we confident enough of

their merit to protect them into perpetuity? Will Walter Gropius's

MetLife Building, looming over Grand Central Terminal, be next on the

list of buildings to be protected?

The problem is that modernist architects espoused a good number of truly

bad ideas, which are far more important than their familiar contempt for

color and ornamentation. At its most fundamental, modernist architecture

intended to break with the past, defy the streetscape, and rend the

urban fabric. In urging that buildings be landmarked, preservationists

are not merely advancing the benefits of modernism's clean, uncluttered

lines. They argue the benefits of what are often modernism's

depredations, such as the super block.

Of course, some of the debate will be settled by deterioration. As a Yale

architectural historian, Vincent Scully, pointed out in 1999, modernists

embraced an aesthetic of impermanence - with the result that most of

their buildings will not survive because they were poorly built. Mies

van der Rohe may have defined architecture as the will of an epoch

translated into space, but much of that will is crumbling beneath its

shoddy materials.

Many of the finest modernist buildings have already been landmarked.

Joseph's Urban's sublime New School for Social Research, for example, on

West 12th Street, is protected by an individual designation. Mayer,

Whittlesley & Glass's Butterfield House, across the street, is protected

by the overarching of the Greenwich Village Historic District. The

best-known modernist buildings were designated when they became

eligible. Gordon Bunshaft's 1952 Lever House on Park Avenue, for

example, was designated a landmark in 1983, a year after eligibility.

Here are a few worthy, undesignated buildings for public discussion:

The Edgar J. Kaufmann Conference Rooms in the penthouse of 809 U.N. Plaza

make up one of only three projects in the country designed by Alvar

Aalto, the Finnish architect. The rooms were commissioned in 1963 by

Edgar J. Kaufmann Jr., the first curator of industrial design at the

Museum of Modern Art and the son of the couple who had commissioned

Frank Lloyd Wright to design Fallingwater in Pennsylvania. The rooms are

a small masterpiece, notes a preservation advocate with the Preservation

League of New York, Caroline Rob Zaleski. "Anywhere else in the world,

these rooms would be a monument," she says.

The Tracey Towers Apartments at 40 West Mosholu Parkway in the Bedford

Park section of the Bronx, designed by Paul Rudolph and Jerold Karlen,

were built between 1967 and 1972. In these moderate-income apartment

towers that opened in 1974, Rudolph deliberately mimicked the striated

surface of the Art and Architecture Building he had designed for Yale.

Somehow, though, they are far more pleasing. This is no minor matter

since they were financed under the state's Mitchell-Lama program, which

severely restricted "extras" in design and architecture in order to keep

costs down for moderate-income households. A fellow with the Municipal

Art Society, Vicki Weiner, notes that Rudolph successfully worked out

the design problems of high-rise living in an urban neighborhood.

Citicorp Center at 153 E. 53rd St. in Midtown, designed by Hugh Stubbins

and completed in 1977, was built during the fiscal crisis that nearly

bankrupted New York. Though its engineering proved to be seriously

flawed, its social mixture worked well: corporate offices above with St.

Peter's Church and jazz center, a landscaped courtyard and galleria, and

a beautifully constructed subway station below. An architect who also

oversees the Web site nyc-architecture.com, Tom Fletcher, calls the

church "an anchor of serenity" and the building itself a "bold presence"

that helped revitalize a tired commercial area.

The Asphalt Green Aqua Center at 1750 York Ave. was designed by Richard

Dattner and completed in 1993. Asphalt Green is so much fun and would be

instantly recognized if the landmarks commission had enjoyability as a

criterion. The original Municipal Asphalt Plant, with its parabolic arch

structure, was designed by Kahn & Jacobs and opened in 1944. In 1968,

the city tried to demolish Asphalt Green, which Robert Moses had called

"the most hideous waterfront structure ever inflicted on a city."

Instead, it was reconfigured by Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum into a

sports center that opened in 1982. After much neighborhood agitation,

Asphalt Green and the sports center were redesigned into the current

complex.

Like Asphalt Green, the city itself needs to adapt, preserving what's best

and discarding what's not. Modernist buildings should be kept or

rejected on their merits - not because they're symbols of their time, or

because eminent architects designed them. Eminent modernists chose to

slash New York's urban fabric with many of their buildings, only a few

of which are worthy of the city they damaged.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |