Map 3 (left) : Brooklyn Community District 3.

Map 4 (middle) : Bed-Stuy according to the Bedford-Stuyvesant

Redevelopment Corporation.

Map 5 (right) : Bed-Stuy according to the Department of Housing

Preservation & Development

History

As Douglass North simply put it: “History matters. It matters not just

because we can learn from the past, but because the present and the

future are connected to the past by the continuity of a society’s

institutions.”(6) Bed-Stuy has a relatively short history as a

community, since its Afro-American and Caribbean population really

started coming to the neighborhood in the1920s.(7) The brief historical

description of the neighborhood which follows aims at demonstrating that

institutions and social capital had little opportunity to develop until

the end of the century. Examining another history, the history of

American slavery, would be needed to understand why immigrants from the

South of the US did not have levels of trust and cooperation among their

community comparable those of other immigrant communities, such as the

Caribbean and African communities. But I will limit myself here to the

history of Bed-Stuy.

The Dutch West India Company established Bedford in 1663. It was a rural

community until the Nineteenth Century(8) when Dutch farmers started

selling land to newcomers. Free African-Americans were among the first

to buy land and settle in the area. Weeksville was named after James

Weeks, an African-American entrepreneur who bought land in 1838 and sold

it to other black settlers.

Weeksville and Carsville are two small closely related black settlements

begun in the 1830s and 1840s. They were located less than a mile from

each other on the former farmland in the Southern portion of Bedford, in

an area bounded approximately by present-day Atlantic Avenue, Ralph

Avenue, Eastern Parkway, and Albany Avenue. By the mid century, these

communities were well formed and had begun to establish schools,

churches, and other institutions of community life.(9)

|

|

Map 6 : Pratt Center for Community & Environmental Development

and Joan Maynard |

These settlements became

a refuge for blacks from New York City during the great Draft Riots in

1863 and kept expanding thereafter.(10)

In the 1860s and 70s an increasing number of wealthy New Yorkers, mainly

from Dutch and German descent, established residence in Bedford. The

urbanization of the neighborhood followed the street plan ratified in

1839, which extended the grid throughout Brooklyn11. Bedford was an

exclusive and highly demanded suburb. Market pressure led to rapid

urbanization of the area: “the suburban district of freestanding frame

and brick homes was gradually transformed into a more urban neighborhood

of brick and brownstone row houses.”12 Instrumental in popularizing the

neighborhood was the construction of the elevated railway lines giving

fast access to Downtown Brooklyn and Manhattan. The housing market

boomed from 1880 to 1920 as Neo Greek, Romanesque, and Queen Ann style

buildings mushroomed all around Bedford.

In the course of a few years, the demographics of the neighborhood

changed dramatically. “[W]hile the brownstone houses of Bedford were

solidly built and long lasting the community itself was to be temporary,

transformed in a few short years by the ceaseless forces of urban

change.”13 Between the wars, and particularly after the Great

Depression, middle and upper class people moved out of the neighborhood.

Real estate value dropped and working class people moved in. Bedford

became less exclusive and more integrated: “Jews, Italians, West

Indians, Irish and other ethnic groups settled in this aging yet still

comparatively attractive neighborhood.”14 Many property owners had

become too poor to keep their homes. Sold because their owners were no

longer able to afford their property taxes, or voluntarily selling their

property before it devaluated further, the brownstones of Bedford

quickly switched hands. Black in-comers filled up the houses abandoned

by previous immigrants. The devaluation of Bedford corresponded to the

massive migratory flux of black Southerners and West Indians to New York

that began in the 1910s and 20s. “From the poverty and social

constraints of the rural South came thousands of black men and women,

seeking the greater opportunities for economic advancement and personal

freedom supposed to exist in northern cities. Bedford became first

choice destination for black immigrants. The existence of communities in

Weeksville, Carrsville, and Fort Green made it easier for other black

immigrants to settle in the area. The construction of the A train in the

1930s made the commute between Harlem and Bedford much easier. Many

people came from uptown to central Brooklyn, which offered more jobs and

better housing.

Property value was dropping fast. A number of white homeowners reacted

by attempting “to persuade residents not to sell to blacks and

encouraged the use of racially exclusive covenants.”15 However, the

white flight was a self-fulfilling prophecy, and totally destabilized

the real estate market. The real winners were not the black immigrants

who purchased the properties, but real-estate traders:

How do slums begin in the cities? Ask the question to some older or

former Bed-Stuy residents and they will be quick to give you a one-word

answer a³blockbusting. Real estate brokers, speculators, professional

blockbusters, not excluding certain banks and mortgage companies are all

considered to follow this practice and hence to be slum builders. Many

stories are told and retold about such incidents of exploitation as

black family forced to pay $20,000 for a house that the realtor had

purchased for $2,000 or $3,000 just the week before. Additionally it was

hard for a black man (or woman) to get a mortgage, many blacks had to

turn to a middleman, who did his “share” in fleecing poor buyers. Thus

the new black owners found themselves faced with an ironic situation:

they had entered into this financial serfdom in order to provide a

better standard of living for their families and themselves. Yet in

order to maintain the homes that were to help to do this, many were

compelled to cut up the older Bedford-Stuyvesant house they had

purchased into “rabbit warrens” renting out the cubicles for whatever

amount they could bring.16

The “slumification” of

the neighborhood really began in the 1930s after the Great Depression as

bankruptcy and poverty spread all over New York. Blacks were the first

fired and last hired. From then on, the neighborhood was pretty much

left to itself by the public authorities until the 1960s when Senator

Robert F. Kennedy toured the dilapidated streets of New York’s

Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood and planted the seeds for what would

become the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation.

Job opportunities at the Navy Yard during the Second World War brought

more black immigrants to what is now known as Bedford-Stuyvesant. The

two neighborhoods, following the same evolution, came to be known as

Bedford-Stuyvesant.

Since the postwar period to our days, racial diversity declined

steadily. The population of Bedford-Stuyvesant went from being 25% black

in 1940 to 50% in 1950, 74% in 196017, 82% in 197018, and to about 85%

since the 1980s. Behind this apparent racial homogeneity lies a variety

of national origins and socio-cultural backgrounds, including, by the

1970s, Puerto Rican, middle class black-Americans, and West Indians.19

The concentration of blacks in Bed-Stuy can be attributed to racial

segregation in housing more than the will of black people to live in

homogeneous community.

Blacks of the 1950s and 1960s were simply unable to buy or rent homes in

large parts of Brooklyn and in many white residential districts

throughout the metropolitan area. Residents and real-estate brokers, in

these areas combined to exclude black families unhampered by the

ineffectively enforced civil rights laws. Bedford-Stuyvesant was one of

the few areas open to blacks.20

In a 1967 survey of the Bed-Stuy community, when asked to choose between

“moving into a block with people of the same race or one with people of

every race”, nearly 4/5 of respondents chose “every race.”21 Despite

rampant segregation and institutional racism thus, the black population

was open to live in a multi-ethnic environment. The schools were not

receiving adequate support, city services, and public works were almost

non-existent, and the police were feared rather than reassuring.

Injustice and poverty led a minority of black-American to endorse a

separatist ideology. Political tension reached its climax in Bed-Stuy

during the Civil Rights Movement, in the late 1960s. It resulted in a

one-day riot on July 29, 1967:

[T]here were serious disturbances at the busy intersection of Fulton and

Nostrand Avenue. Over one thousand young blacks (age fifteen to

seventeen years) had broken windows, set buildings aflame, ripped

storefront gates, stolen and looted on Nostrand Avenue between Atlantic

and Fulton. ? fourteen people had been arrested; a full alert had been

put on in Bedford-Stuyvesant. The 20th Tactical Patrol Force had been

sent into Bedford-Stuyvesant because there had been four consecutive

nights of sporadic violence in Spanish Harlem.22

Most rioters were disillusioned second-generation teenagers. In 1967,

the “need for jobs and fuller employment” was cited by 41% of surveyed

residents as a main problem23. Perhaps the high percentage of recent

immigrants in Bed-Stuy prevented the riots from reaching the scale of

the riots in Harlem, Newark, Los Angeles, or Detroit. Immigrants are

often too busy trying to make it to engage in political action.

These events happened shortly after Senator Robert F. Kennedy had toured

Bed-Stuy and initiated the first Community Development Corporation (CDC)

in the country, the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation. Senator

Kennedy convinced eminent personalities of the political and business

world to join the board of the Restoration Corporation, thus insuring

maximum credibility and enabling it to become the first CDC to receive

federal funds.

However, the Restoration Corporation did not succeed in lifting Bed-Stuy

out of poverty. Not all programs succeeded, as the failure of the

following IBM project illustrates. One of the chairmen of IBM, Thomas B.

Watson, was also a board member at the Restoration Corporation. Mr.

Watson was instrumental in opening an assembly plant employing four

hundred people. Unfortunately, the plant failed to show adequate returns

on investment and was finally converted to public housing (after an

unsuccessful attempt to transfer the ownership to the employees). The

“additional cost, above and beyond that which a similar plant elsewhere

would have required, has militated against the likelihood that other

corporations would locate there.”24

It seems that the Restoration Corporation was no exception to the

general failure of CDCs to develop distressed neighborhoods. David Rusk

notes that “in cities across the country, the 34 target areas served by

the most successful CDCs as a group still became poorer, fell farther

behind regional income levels and lost real buying power.”25 The same

observation was also made by Margaret E. Dewar: “Most evaluations

conclude that state and local business financing to stimulate economic

development outside big cities does not achieve the explicit goals ?

Programs aimed at specific distressed geographic areas show almost no

effects on the growth of these areas.”26 In other words, if citywide

programs can have an impact on neighborhoods growth, no evidence proves

that programs limited to specific locations bring results. It is hard,

however, to evaluate the impact of CDCs on depressed neighborhoods

because firstly their programs might have long-term a reach rather than

short-term effects and secondly it is impossible to evaluate how much

worse the neighborhood could be had the CDCs not being present.

However, even if the Restoration Corporation did not save Bed-Stuy, the

money and expertise it channeled to the neighborhood have had a long

lasting effect on the neighborhood. Its renovation and mortgages

programs had a tremendous impact on the longer-term appreciation of the

housing stock and stimulated private re-investment. The Restoration

Corporation could even take a good part of the credit (or the blame?)

for the current boom in real-estate value, since its revitalization of

the neighborhood stimulated private investment.

The Restoration Corporation brought a great deal of linking capital to

the community27: it re-established formal connections with some

mainstream public and private institutions. It was a welcomed

manifestation of good will from the authorities, even though much more

was needed to restore the community’s trust in public institutions.

Years of economic poverty, financial redlining, political segregation,

and legal injustice have definitively done much to “ghettoize” the

community. As World Bank social scientist Michael Woolcock noted,

“hostile or indifferent government have a profoundly different effect on

community life (and development projects), for example, than government

that respect civil liberties, uphold the rule of law and resist

corruption.”28 Henry L. Gates of the African-American Studies department

of Harvard, suggests indeed that much of the “gangster culture” and

“show me the money” attitude that came to epitomize black ghettos such

as Bed-Stuy has deep roots in the political and institutional history of

American society, starting at the White House.29

On top of existing economic and social problems came the devastating

crack and heroin epidemics, which began during the 1970s and late 1980s.

Drugs were and still are a way out of boredom and bitterness for many

unemployed and disillusioned youth, and also the most direct (sometimes

the only) way to make money. “The quest for manhood is not a simple

thing in any community, but in such areas as Bed-Stuy, in Brooklyn it is

as difficult as an escape from prison.”30 Indeed, many youth of Bed-Stuy

grew up with weakened or non-existent social and familial structures:

As a result action is what happens on the street, and when a youth

graduates from them, he has his diploma into adulthood but he is not

necessarily a man. His entire experience is likely to be circumscribed

by a series of predictable dehumanizing incidents: gang rumbles, quickie

sex in tenement hallways, petty thievery, menial jobs at meager pay, and

a number of abusive confrontations with the law. Indeed, his

relationship with the police is the most predictable of all. It is also

likely to be the most brutal.31

Poor neighborhoods become poverty machines that generate poverty

itself.32 Bed-Stuy seemed to be locked up in a vicious cycle of poverty

until the early 1990s. Redlining by banks made it difficulty to start

new businesses or even to save money. The unavailability of capital in

the neighborhood prevented investment and thus the creation of more

capital. It constituted an absolute constraint on growth. Poverty itself

has an anti-growth effect. Poor are often unable to develop skills for

the market and are less responsive to opportunities.33 Given this

seemingly hopeless situation, many of the most upwardly mobile residents

moved out of the neighborhood as soon as they could, leaving behind more

empty houses, broken windows, poverty, and despair.

Poverty, hopelessness and drugs congregated to create “high rate of

crime and violence that [in turn] generate[d] low levels of trust and

cooperation among residents.”34 However, it seems that as a response to

a hostile environment and in the absence of mainstream institutions

linking Bed-Stuy to the rest of society, solidarity and informal

institutions got stronger. But the social capital needed to support

economic institutions in the neighborhood was definitively lacking. The

legal system was not trusted, and connections to the rest of society

weak. Reliance and cooperation with the immediate entourage was

therefore a matter of survival, to the youth it could mean sticking to

the gang, and to the elderly, reliance on familial and religious circle.

In other words bridging capital was low but bonding capital high35.

|

|

|

The numerous religious communities of today’s Bed-Stuy inherited

some beautiful churches from the upper-middle class population

of the early twentieth century. |

Community organizations

such as charities and churches have a very important role in Bed-Stuy.

They have been instrumental in preserving some sense of pride and

solidarity in the community and to a large extent filled up “structural

holes36 left by the lack of formal political and economic institutions.

In an interview I had with Assemblywoman Robinson, who represents the

57th precinct (which includes Bed-Stuy), she recalls the great benefits

brought by churches to the community. They bound religious communities

together, and many have direct social programs such as food and clothing

distribution, affordable housing development, and financial support for

small business.

Today the ghetto is still in Bed-Stuy, but Bed-Stuy is out of the

ghetto: Nearly a quarter of households have an income over $50,000

(compared to only one eighth in 1990)37. Real-estate value has doubled

or tripled in the last five years. The infant mortality rate decreased

from 21 per thousand in 1990 to 9.1in 199938. Crime rate in the 79th and

81st Precinct covering Bed-Stuy has decreased by 60% and 58%

respectively since 199339. The war on crime launched by the Giuliani

administration since 1993 definitively deserves a large part of the

credit for this dramatic decreases. While reduction of criminal offenses

in the Bed-Stuy area corresponds to the citywide numbers, other

neighborhoods with similar reduction in crime rates did not experience

the same income growth and quality of life improvement. Other macro

factors for the recent development of Bed-Stuy include the American

economic growth of the 1990s. A little share of the wealth created by

Wall Street and Midtown trickled down to Bed-Stuy.

The history of Bed-Stuy is the history of the trial and tribulations of

its people. By an irony of history one of the most beautiful

neighborhoods of New York City became the home of some of those who have

suffered most from segregation and injustice. Residents of Bed-Stuy are

increasingly recognizing the value of their neighborhood, as newcomers

keep flowing in. Today, the neighborhood is developing from the bottom,

with poor immigrants striving to make it and running small businesses,

and from the top with newcomers bringing investment and hope. The next

section will focus on immigrants coming from poor countries. The history

of Solomon and Malik will illustrate the energy and entrepreneurial

spirit of immigrants from the Caribbean and Africa.

Immigration

Poor immigrants kept coming from the Caribbean, but also from the French

Antilles, Latin America, and Africa throughout the twentieth century. At

the same time, second and third generation black Southerners and

Caribbean with higher educational and income levels came (or came back)

during the 1990s, bringing more purchasing power to the neighborhood. I

will first describe the contribution of the Caribbean and African

immigrants to the recent development of the neighborhood, discussing

along the way the costs and benefits of the informal economy for which

these groups are often held responsible. Then I will analyze the impact

of higher-income newcomers, from New York and the rest of the world.

The West Indian population started moving into the neighborhood as early

as the 1920s. It seems that they have been among the most successful

segment of the community. As a Caribbean resident stated: “ the Bed-Stuy

West Indian would be among the most ambitious and hard-working people

one would find anywhere. This seems to be true wherever the West Indian

finds himself, and however incongruous his ambitious behavior may be

when contrasted to others in the community.”40 Mr. Senckler,

vice-president of the Restoration Corporation, himself a

second-generation Caribbean born and raised in New York, calls

immigrants the “backbone of the community”. He believes that they bring

a positive energy to the neighborhood. “They are hard working people,

with a strong desire to succeed.” Mr. Senckler also emphasizes the

cultural contribution of immigrants to the community.

|

|

The picture shows a gas truck owned by a Caribbean driver in

Bed-Stuy. The Drawing represents the Lion of Judah, a biblical

symbol of the Rastafarian religion and culture. The flag with

the colors of Ethiopia reading “positive” is representative of

the attitude of many Caribbean descendent. |

Many businesses in

Bed-Stuy are owned by people of Caribbean descent, typically health food

stores, take-away restaurants and house repair. The Caribbean population

is often perceived as having strong moral values and entrepreneurial

skills. Many Caribbean families choose to invest in their children’s

education and send them to religious or private schools. This has paid

off already as an increasing number of second generation Caribbeans who

came from poor immigrant families, climbed up the social ladder to

middle and upper-middle class professions and incomes. Mr. Senckler

himself exemplifies this pattern of success. As a resident quoted by

Mary Monomi bluntly put it: “It is one thing to say that there are

blacks in high positions in the police and fire departments and in the

school system, and those who own some sort of business. It is quite

another thing to check it out and see that most of those so-called

success stories are about immigrants whose formative years were spent on

some small foreign islands in the Caribbean a³or the children of those

immigrants.”41 However this statement is dated (1973) and probably says

more about the pride of the respondent than anything else. The Caribbean

and African-American cultures have merged to a large extent in Bed-Stuy.

Assemblywoman Robinson, who praises immigrants for the cultures and

value they bring, doesn’t like to separate black-American and Caribbean

people: “both share a common history and are the original people of

Bed-Stuy.’

Solomon’s story exemplifies both the entrepreneurial spirit of Caribbean

immigrants and their integration. Bricklayer and brownstone owner,

Solomon came to New York in the 1970s from Trinidad. He first settled in

Queens, in a neighborhood where he could find good schools for his two

children. After working and saving money for years, he decided to invest

in a house. His family and friends thought he had lost his mind when he

bought a brownstone in Bed-Stuy about six years ago in the mid 1990s,

before the market got hot. But Solomon, who built houses for many years,

knows how to recognize quality. Once, after I referred to the new Trump

tower as a “high-class residential building”, Solomon (otherwise very

well behaved) replied impulsively: “High-class? B? S?! I have been

working on these buildings. The walls are paper-thin. If you throw a

kick, you end up in the neighbors’ dinning room! Now look at these walls

(pointing to the brick walls of his brownstone that he had stripped of

all wallpaper and painting), this is quality. They don’t make houses

like that no more.” He has a point: Bed-Stuy brownstones are high-class.

Unfortunately, most of them are in a bad shape. Solomon entirely

renovated his brownstone himself, working every day after work. At one

point, he had pierced holes in the ceilings, the floor, and the walls to

fix the water pipes and electricity and take away the layers of

wallpaper, paint, carpet added throughout the years. Solomon is now

renting the two top floors of his brownstone and talking about retiring

to Trinidad.

If Solomon’s dreadlocks hint at his Caribbean origins, no exterior signs

would attest of his son’s ancestry. Dressed in the straight up hip-hop

fashion of Bed-Stuy, he looks like a³and actually is a³ an American kid.

As Greg Donaldson, explained in an interview42: “Most Caribbean youth

adopt the African-American culture as soon as they go to school and

socialize.” Youth might keep their Caribbean roots inside, but they very

quick to adapt to the local American culture. A few years older,

Solomon’s daughter might be closer to her origins in style, but she also

definitively integrated the local culture. Solomon mentioned that most

of her friends are from their former neighborhood, including her white

boyfriend. “If it is love, it cannot be wrong”.

A new wave of immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa has recently joined the

community. The Pratt Area Community Council ancestry figures show a

large increase in African residents from 1990 to 2000. According to one

African vendor I talked to, between one and two thirds of the African

residents in Bed-Stuy are undocumented. One thing is sure: the African

presence is very visible in the streets of Bed-Stuy, particularly along

the Fulton street commercial strip, where many shops and restaurants are

owned or managed by Africans. Bed-Stuy has a high concentration of

African Muslims. A mosque situated right at the corner of Bedford and

Fulton is always busy with street activity. The segment of Fulton

between Bedford and Franklin Avenues has about a dozen halal restaurants

and bakeries, serving some of the best quality food in the neighborhood.

The African Muslim community seems to be well integrated to other

Muslims communities, such as the Indonesians and Pakistanis.

|

|

“Muslim Street”, on Fulton Avenue between Bedford and Franklin.

The image shows the mosque at the corner next to a clothing

shop, a Halal restaurant and a bakery. |

The African community

itself is divided into sub-communities. Members of each sub-community

might have strong tights with each other, for instance most French

speaking Africans know each other, however they seem relatively weakly

connected to the black-American community. Some long-term residents

resent the apparent lack of involvement in the community of the African

Diaspora. Crystal, a black-American storeowner, notes that African

immigrants do not seem to do much effort to integrate the rest of the

community. Many of them are single men or women with families back in

Africa. They are mainly in New York to make money to send back home. As

they do not plan to stay in the community forever, they have little

incentive to get involved in communal life. Moreover, many have several

jobs, or work every day of the week. If they do not manage to engage in

social activities, they certainly try hard to supply goods and services

demanded by the community. Malik, an African CD vendor on Bedford

Avenue, argues that immigrants like him cannot afford to let

opportunities go by, “we are more willing to take risks and work hard

than others because we have more pressure to make it.” He still has a

family to look after in Africa. With the little cash he makes, he sends

eight children to school in Burkina Faso.

Economics of immigration

Immigration made New York City. Since incoming immigrants are generally

poor, their economic impact on neighborhoods such as Bed-Stuy do not

directly boost income statistics. However, they indirectly contribute to

the economy. In the short term, immigration from poor countries might

appear to limit economic development since it increases the poverty

level and puts pressure on the infrastructure and social services. In

this section, I will first analyze the benefits of immigration, which

include economic dynamism, increased spending, cheap labor, small

business creation, and innovation. Then I will evaluate its cost,

including, loss of jobs for the local population, criminal activity,

infrastructure congestion, social burden, and the informalization of the

economy.

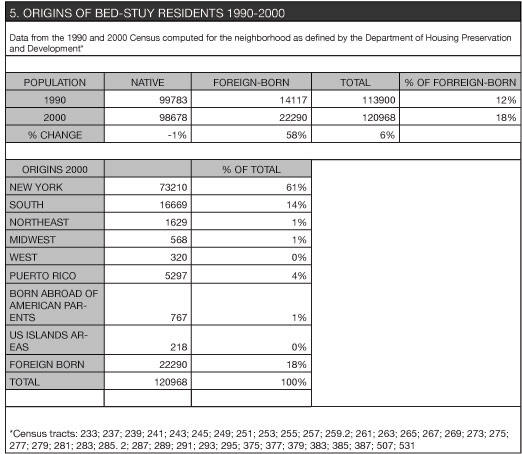

Immigrants, legal and illegal, are increasingly numerous in Bed-Stuy.

Using the definition of the neighborhood boundaries of the Department of

Housing Preservation and Development (narrower than Community District

3), and the census data from 1990 and 2000, the population of the

neighborhood increased by 6%. The foreign-born population increased by

58%, faster than the local population. Foreign-borns are now

representing 18% of the total population in 2000 as compared to 12% in

199043. The data is uncertain, since a good proportion of the

foreign-born population, particularly illegal immigrants, are not

accounted for by official statistics.44

Because they are under extreme pressure to “make it”, immigrants often

seize opportunities and take jobs that locals, even poor, do not want.

This entrepreneurial “do-it-yourself” spirit directly benefits the local

economy in different ways. First it creates a pool of cheap labor that

reduces production costs and increases the productivity of capital,

making local business more competitive.45 For instance, shop owners can

hire staff that will help them serve more than one client at the time,

or allow them to take care of other businesses. Entrepreneurs employing

cheap immigrant labor can reinvest a larger part of their capital in

their business. As development economist Slobodan Djajic puts it:

availability of cheap clandestine labor represents a significant

advantage for entrepreneurs initiating new businesses and reduces the

risk of embarking on new ventures. To the extent that it promotes

start-ups of small businesses, the availability of illegal aliens in the

economy may be an important factor in stimulating economic growth,

investment, and a competitive business environment. In turn, a healthy

and dynamic small business sector is at the heart of jobs creation for

the native workers in most economies.46

Immigrants are consumers, renters, and taxpayers. As the population

increases, consumption rises, thus local businesses directly benefit

from immigrants. As they create businesses themselves, they invest their

revenues to purchase stock or hire workers. Immigrants also spend money

on residential and commercial rents. Rental of retail space to immigrant

entrepreneurs directly increases the income of local owners. Finally,

they pay taxes, whether they are legal or clandestine. Even businesseses

owned by illegal immigrants generate tax revenue through the automatic

tax withholding system. Although Malik is himself in an irregular

working situation, his business is official registered and taxed.

Immigrants are good at filling up gaps in demand. As Malik puts it, “we

see opportunities natives don’t see, and we are willing to do the job.”

The hat or incense stalls on Fulton or Nostrand Avenues

characteristically fill up little spaces unusable by the bigger shops.

Moreover, immigrant vendors, using their community networks, are often

good at satisfying specific demands, such as finding the CD of a

particular musician or the hat of a particular baseball team.

The entrepreneurial and “self-help” spirit of immigrants stimulates

experimentation and innovation. For instance, a general utility store on

Nostrand Avenue just moved its facade inward in order to put an outdoor

stall selling inexpensive winter goods. This allowed the store to take

full advantage of the pedestrian traffic. Consumers do not have to step

in; they can just purchase a pair of gloves on their way to the subway.

Interestingly this innovation was inspired by street vendors who rely on

“opportunity” rather than “destination” shopping. Another example of

creative innovation is the delicious “bean pie” invented by a Muslim

baker on Fulton. Unique in taste, it can be found only in Bed-Stuy (at

least that is what the baker says!).

In Bed-Stuy, as elsewhere, immigrants are “vital to progress in carrying

ideas from place to place.”47 Some examples are: specialty shops selling

authentic African fabric and crafts, Caribbean bookstores and health

stores, Halal restaurants, and Southern Soul food restaurants. They all

bring new cultures and lifestyles to the neighborhood and stimulate the

local economy.

If immigration brings a positive spirit to the neighborhood and

stimulates local economic activity, it also has its costs. Firstly,

Assemblywoman Robinson observes that African and Indian communities

would rather trade among each other. She argues that the money does not

circulate, going straight from the hands of residents to the pockets of

foreign merchants. It is probable that many business transactions are

made within the community. The immigrants’ own communities are obviously

a first choice business network with higher levels of cooperation and

trust. Many recent immigrants do not even speak English. When he first

arrived to New York four years ago, Malik did not even know how to order

food. Four years later he is fluent and trades everyday with locals. The

pirate CDs he sells are produced locally by indigenous residents.

However, he spends little of his money in local shops and business. This

is because he hardly ever spends any money for non-essential goods and

services. Most of the money he earns is sent abroad to his family. It is

probably generally true that immigrant workers send a good share of

their revenues abroad. This is good for Africa and South America, but on

the first sight seems to channel money away from Bed-Stuy.

[M]any trade economists argue that humanity as a whole benefits

enormously from migration. Alan Winters of Britain’s Sussex University,

in a study for the Commonwealth Secretariat, has tried to quantify these

gains. He concludes that, if the rich countries raised the number of

foreign workers that they allowed in temporarily by the equivalent of 3%

of their existing workforce, world welfare would improve by more than

$150 billion a year. That is bigger, he points out, than the gains from

any imaginable liberalization of trade in goods.48

Therefore, in a global, long-term perspective, the money sent abroad

also contributes to local wealth. A richer world is good for the US

because it expands the market for its export goods. Moreover, better

distribution of wealth in the world reduces the need of residents of

poor countries to immigrate. Although the connection is quite direct, it

seems far remote from the everyday economic life of Bed-Stuy. Also, if

immigrant merchants send abroad a portion of their revenue they still

spend a good share of it locally in business investment and living

expenses.

Another commonly perceived cost of immigration is that it takes jobs

away from the locals. As immigrants are willing to work more and for

less, it is believed that they “take jobs held by [or destined to]

natives and thereby increase native unemployment.”49 Most economists

reject this argument for being too simplistic: “Immigrants not only take

jobs but they also make jobs, in two ways: First, their spending

increases the demand for labor, leading to new hires. And second, they

frequently open small businesses that are a main source of jobs.”50

Moreover, the assumption that illegal immigrants are more likely to

indulge in criminal activity than natives seems to be false. Illegal

residency produces a paradoxical effect. As it increases precariousness

and subjects immigrants to the arbitrariness of institutions, the

police, or employers, it forces them to lead a honest life.51

Mr. Senckler of the Bed-Stuy Restoration Corporation points out that

newcomers represent a supplementary cost for the community in the

following areas: education, sanitation, housing, and transportation.

“The standard presumption is that additional people a³children or

immigrants- have a negative effect upon the incomes of the rest of the

people. The usual reasoning is diminishing fixed stocks of agricultural

and industrial and social capital, together with the dependency burden

of additional children and the consequent need for additional

demographic investment.”52 The main burden associated to the demographic

increase caused by immigration is on the school system:

Immigrant children and their use of educational services have been at

the center of the public debate on the public-sector impact of illegal

immigrants. According to Weintraub and Caderas (1984), 85 to 93 percent

of the cost of the public services used by illegal immigrants goes for

education.53

However, it appears that the contribution made by immigrants to the

public coffers is higher on average than their cost. A “magisterial

study in 1997 of the economic impacts of immigration, by America’s

National Research Council, found that first-generation immigrants

imposed an average net fiscal cost of $3,000 at present discounted

value; but the second generation yielded a $80,000 fiscal gain.”54

Nevertheless, if immigrants directly benefit the government through

increased tax revenue, they might represent a burden to the community as

they create an additional pressure on existing infrastructure,

especially if they do not spend their earnings in the neighborhood.

Therefore, to truly benefit from immigration, Bed-Stuy should have

enough public subsidies to expand its infrastructure in line with its

demographic increase.

Another cost of illegal immigration is the one paid by the illegal

immigrants themselves. Informal workers have the hardest working

conditions and lowest wages. Malik works from 9 AM to 9 PM, seven days a

week, and has not had a break in four years. Living close to subsistence

level, he cannot afford to take holidays. Moreover, the very precarious

condition of his status and activity, and his total reliance on it,

makes him very vulnerable to exploitation from potential lenders, his

landlord, and even clients. He lives under the permanent threat of

losing everything. He has no health insurance, social security, or

pension, and cannot go in and out of the country. The precariousness of

his situation prevents him from investing much. The risk of losing

everything usually outweighs potential future gains. Therefore

precariousness itself prevents development.

|

|

The last two commerce open at 7 PM on Nostrand Avenue, between

Fulton and Macon, are the hat shops owned by Africa immigrants. |

Finally, immigrants,

particularly undeclared ones, are often blamed for sustaining a

secondary, informal economy. Assemblywoman Robinson estimates that the

portion of the local economy which is “unregulated by the institutions

of society”, to use Castells and Portes’ definition, is “rather

important” in Bed-Stuy.

“Immigrant communities are a key location for informal activities

meeting both internal and external demand for goods and services.”55

However no systematic relationship between immigration and the informal

economy can be made. Many illegal immigrants in Bed-Stuy and New York

City run declared, tax-generating businesses. The informal economy is

not, as I will try to demonstrate, a direct consequence of immigration.

As Saskia Sassen puts its:

Immigrants, in so far as they tend to form communities, may be in a

favorable position to seize the opportunities represented by

informalization. But the opportunities are not necessarily created by

immigrants. They may well be structured outcome of current trends in the

advanced industrialized economies.56

Informal Economy

Indeed, a current trend in advanced industrial economies is the

dismantling of the welfare state. Since 1990, the number of people

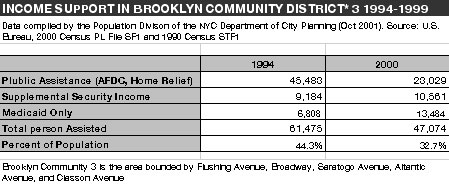

qualifying for Public Assistance in Community District 3 has declined

from 45,483 to 23,029.57 It would thus appear, at first sight, that

poverty decreased in Bed-Stuy. According to the Brooklyn Chamber of

Commerce report58, the percentage of households earning less than

$10,000 annually went from 35% in 1990 to 24% in 200059. Converting to

2000 dollars, we can restate this statistic above this way: In 1990

18,986 households earned less than $13,175 (in 2000 dollars) and in

2000, 12,729 households earned less than $10,000. It would seem

therefore that poverty in absolute numbers has not significantly

decreased. What has decreased, however, is the number of people

qualifying for welfare benefits. Indeed, from 54% in 1997, the rejection

rate for welfare in New York City rose to 75% in 1998.60

As social safety nets disappear, those who cannot, or do not want to

join the pool of minimum-wage workers feed the informal sector:

In their quest for survival, [agents] have connected with a more

flexible, ad hoc form of economic activity that, while reviving old

methods of primitive exploitation, also provides more room for personal

interaction. The small-scale and face-to-face features of these

activities make living through the crisis a more manageable experience

than waiting in line for relief from impersonal bureaucracies.61

|

The informal street

vendors, who were all over Fulton Avenue until 2001, are the best

example of the vitality and negative externalities of the informal

economy in Bed-Stuy. The anarchic street market has now been “cleaned

up” by the authorities. Now, a couple of street vendors occasionally

sell sweaters or CDs, but it is nothing like it used to be. The street

vendors who had “been a permanent fixture on Fulton Street for decades,

have been relocated from the sidewalks near the intersection of Nostrand

Avenue and Fulton Street to a central location known as the Bed-Stuy

Coop Market, on the corner of Albany and Fulton Streets.”62 Some liked

the informal market and others hated it, but no one was indifferent.

I asked Jahdan, a local musician who has know the area for as long as he

can remember, how the neighborhood had changed in the recent years:

“Before, it was open to merchants, but they chased them out of Fulton.

Now they need an authorization. Street vendors are outlawed. Fulton

market sold products for the community. It was a strong economic,

social, and cultural space.” Delie, another young resident, makes the

same analysis: “Stopping the market was negative for the community

because it prevented people to make money legally.” He remembers

merchants selling clothes, watches, house utilities, everything

inexpensive. The market was bringing black people of different origins

together, interacting freely and openly. It was a lively cultural and

social scene.

Crystal and Charles, homeowners, disagree. They argue that street

vendors were often selling illegal products, and evading taxes. Charles

says that they were downgrading the street and preventing upper scale

businesses from coming to Bed-Stuy. It congested the street and made it

hard for people and cars to circulate. Crystal didn’t like its aspect.

It was messy and gave a bad image of the neighborhood. Its existence was

a disincentive to rent unoccupied storefronts. Finally, they argue,

street vendors constituted a disloyal competition against established

regular businesses.

Fulton First is an initiative of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce,

financed by the Fleet Bank, the Giuliani Administration, and the New

York City Department of Business Services, aiming at revitalizing Fulton

Avenue. This nearly $4 million plan will redesign the look and feel of

the Avenue “adding lighting fixtures, street furniture, structural

design elements, and traffic flow through the commercial corridor.”63

|

|

About half of the tents provided by the Fulton First Initiative

to street merchants remain empty during the week. |

The first visible action

of Fulton First was the evacuation of street merchants by the police. A

new place was given to street vendors at the corner of Albany and

Nostrand. I have been there a few times during the week and it is pretty

quiet, to say the least. There were about 15 vendors and about half of

the stands were closed. I bought a dubplate mix-CD, a poster and three

pairs of socks for less than fifteen dollars. The market is organized

and orderly but the dynamism seems to be gone. Jahdan believes it was

better for the community when the merchants were not taxed and

controlled. “Let the people do it. People organize the market better

than the City.” Classical economics since Adam Smith agrees:

Smith believed that individual welfare rather than national power was

the correct goal; he thus advocated that trade should be free of

government restrictions. When individuals were free to pursue

self-interest, the “invisible hand” of rivalry or competition would

become more effective than the state as a regulator of economic life.64

The informal market of Bed-Stuy was a perfect example of what happens

when economic agents trade without regulations: creative chaos. Creative

because the free interaction of a multiplicity of vendors and buyers

created a self-sustaining economy out of nothing. Chaos because in an

uncontrolled market, no one is individually responsible for the mess

collectively generated. Street congestion is an example of negative

externality produced by unregulated street markets.

The informal economy is the purest expression of the free market. It

exists spontaneously wherever the formal regulated economy is not:

[i]t is only because there is a formal economy (i.e., an institutional

framework of economic activity) that we can speak of an “informal” one.

In an ideal market economy, with no regulation of any kind, the

distinction between formal and informal would lose meaning since all

activities would be performed in the manner now called informal. At the

opposite pole, the more a society institutionalizes its economic

activities following relatively defined power relationship and the more

individual actors try to escape this institutionalized logic, the

sharper the divide between the two sectors.65

The informal sector emerged in Bed-Stuy as a result of the breakdown of

mainstream economic and social institutions and poverty. In the same way

churches and other non-profit organizations filled up structural holes

in the social fabric, informal businesses emerged opportunistically (one

could even say organically) to fill the economic void. The informal

sector is thus firstly a response to the lack of a formal sector. If

there were a Blockbuster in Bed-Stuy, there would probably be fewer

video vendors in the streets. The informal sector is a product of

low-income consumers’ demand and low-income suppliers who cannot find

adequate sources of income in the formal sector.

On the supply side, the struggle for survival pushes “street

entrepreneurs” to reproduce and sell any kind of goods and services they

can sell. Informal street vendors would certainly prefer to have a

steady income, job security, a pension, and health insurance rather than

living in precariousness. However, the absence of economic opportunities

in the formal sector draws many to the informal sector. Sometimes, as

the quote above stated, regulations can keep people from setting up

legal businesses. For instance, some foreigners might not be able to go

through the procedures required to set up a legal business. Illegal

immigrants might equally be barred from regulating their business for

fear of being expelled. As Steve Mariotti, founder of the National

Foundation for Teaching Entrepreneurship, states:

The minority entrepreneur usually ends up being his own lawyer and

accountant ? The paperwork, cost, and confusion ? drive would-be

entrepreneurs away from certainty and down a slippery slope. They

develop contempt for the government, because they no longer see it as

their ally. That drives people into the underground economy, where there

are no contracts ? Once an entrepreneur moves into the balkanized a³and

chaotica³ underground economy, growing the business is not a viable

option. 66

On the demand side, the need for cheap goods and services feeds the

informal sector. Should a Blockbuster open in Bed-Stuy, it would need to

compete with street vendors selling pirated movies for five dollars.

Since the purchasing power of the local population is lower than in the

rest of the city, market forces naturally drive down the price of goods

and services closer to their marginal cost of production, and closer to

the subsistence level of the producer and distributor. Informal

entrepreneurs are good at fulfilling local demand at competitive prices.

The redundancy of many street businesses, such as CD and hat vendors

insures a quasi-perfect competitive market, which keeps the price near

the margin. Also, the highly open, unstable, and opportunistic informal

small-business environment of Bed-Stuy prevents the formation of price

cartels, and therefore prevents artificial price inflation. The informal

sector is thus closer to the textbook model of perfect competition than

the formal sector because in the formal sector, laws and regulations

artificially maintain the price of goods and services well above the

marginal cost of production.

Such a local economic base may well represent a mechanism for maximizing

the returns on whatever resources are available in the communities

involved. In this regard, they may contribute to stabilize low-income

areas by providing jobs, entrepreneurship opportunities and enough

diversity to maximize the recirculation of money spent on wages, goods

or services inside the community where the jobs are located and the

goods and services produced.67

Low-income consumers are not the only ones benefiting from the lower

prices of the informal economy. The middle-class itself benefits and

promotes the informal sector. Saskia Sassen notes that gentrifying

neighborhoods tend to have high levels of informal economic activity. A

source of informal activity is the rapid increase in the volume of

renovations, alterations, and small scale new construction associated

with the transformation of many areas of the city from low-income, often

dilapidated neighborhoods into higher income commercial and residential

areas ? The volume of work, its small scale, its labor intensity and

high skill content, and the short-term nature of each project all were

conducive to a heavy incidence of informal work.68

Craftsmanship is definitely highly demanded in Bed-Stuy, fueled by the

mix of a deteriorated housing stock and booming real-estate market.

According to the Department of Housing’s statistics, only 49% of

residential buildings are in good or excellent condition. This is the

second lowest score in Brooklyn after Bushwick. 37% of residential

buildings are judged to be in fair condition, and 13.5% in poor

condition, the second highest percentage after Brownsville Ocean Hill.69

There is plenty of maintenance work to do and, according to Charles,

brownstone owner; skilled labor is lacking or expensive. Informal

contractors are found from word of mouth, and are usually freelance and

self-employed. Revenues from house repair typically go undeclared.

Other sectors with high concentration of informal activity include “the

Gypsy cabs [which are] serving areas not served by the regular cabs,

informal neighborhood child-care centers, low-cost furniture

manufacturing shops, and a whole range of other activities providing

personal services and goods.”70

The informal sector is therefore not a problem in itself, but rather the

market solution to poverty and exclusion. The lower purchasing power of

many Bed-Stuy residents stimulated the growth of a market of

substitution. Informality reduces the cost of production and

distribution through tax evasion and proximity to the consumer. The

structural breakdown of economic and social institutions such as the

welfare state has also contributed to the expansion of the informal

sector.

Libertarian economists believe that the unregulated market is the best

way to maximize economic efficiency. The economy, they argue, is like an

ecosystem. Exterior intervention can only harm the perfect

self-organization of the free market. The problem is that, as Adam Smith

noted when he developed his invisible hand theory, the free market has

negative externalities such as labor exploitation and environmental

degradation. Moreover, the unregulated market can sometimes get stuck at

sub-optimal levels. Intervention is needed to help the market grow in

the desired direction. As Paul Krugman ironically puts it:

The economy is an ecosystem, like a tropical rainforest! And what could

be worse than trying to control a tropical rainforest from the top down?

You wouldn’t try to control an ecosystem, wiping out species you didn’t

like and promoting ones you did, would you? Well, actually, you probably

would. I think it’s called “agriculture.”71

This comment helps us to look at the informal economy of Bed-Stuy from

another angle. It should neither be curbed nor be seen as a ready-made

solution requiring no intervention. Its positive outcomes and negative

externalities need to be recognized and dealt with. Its most positive

aspect is that it generates income for many residents and provides goods

and services that would not otherwise be available or affordable to the

community. Informal workers and entrepreneurs should be assisted in

their effort to formalize their businesses. Negative externalities need

to be reduced as much as possible without taking away the positive

outcomes. For instance, the displacement of street vendors to the Albany

square destroyed the previous dynamism of the market. I will suggest

possible ways to preserve the benefits of the informal economy while

reducing its negative aspects in the last section of this paper.

|

|

A renovated brownstone in Bed-Stuy, right next to a board-up

property. The sign reads: “Please keep your block clean, Filth

is lack of pride”. |

To conclude this section

on immigration and informal economy, I would say that, while illegal

immigrants are sometimes drawn to the informal sector by lack of choice,

the informal economy itself did not develop as a “consequence of the

large influx of Third World immigrants and their propensities to

replicate survival strategies typical of home countries.”72 But rather

as a result of the high poverty level existing in Bed-Stuy prior to

their arrival. Far from being a nuisance to the neighborhood,

immigrants, legal and illegal, are a source of growth and change.

Adequate policies are needed to maximize the positive input of

immigrants to the community. The striving small business environment and

the availability of cheap goods and services contribute to the

incremental development of the neighborhood. How many brownstones would

have been privately renovated if the only available craftspeople were

working at Manhattan wages? The self-help attitude of many poor

immigrants and natives has allowed the emergence of a solid economic

base in the neighborhood. The consolidation of this economic base has,

in turn, a stabilizing effect on the social environment, strengthening

social institutions and indirectly setting the context for in-migration

of higher income people.

Newcomers

In the next section, I will consider the factors that turned Bed-Stuy

into an attractive residential location, then portray some

representative newcomers. I already described how the incremental

economic development of the neighborhood, significant reduction of crime

and citywide economic growth improved Bed-Stuy’s physical and economic

condition. These factors, combined with a very tight citywide housing

market during the late 1990s, led an increasing number of people to

chose Bed-Stuy. The work of the Restoration Corporation as well as other

agencies, including the Department of Housing, also has to be accounted

for. The growing black middle-class willing to invest in a home has also

been instrumental in regenerating Bed-Stuy. All these factors contribute

to attract more newcomers. The atmosphere of the neighborhood is

changing. In the words of a local reporter:

On every block, around every corner, there’s a demolition or renovation

project going on; a dumpster filled with the innards of some long

abandoned, burnt out or recently purchased dwelling. (How many scaffolds

did you walk under today?) Those little quality of life issues, like the

refurbishing of those glass and crack vial gardens into viable

playgrounds, are finally being addressed.73

The Restoration Corporation has largely contributed to the appreciation

of the housing stock through its renovation and mortgages programs. In a

little more than thirty years of activity, “it has renovated 4,200 homes

covering 150 blocks and provided more than $250 million in home

mortgages and rehabilitation loans to neighborhood homeowners.”74 In

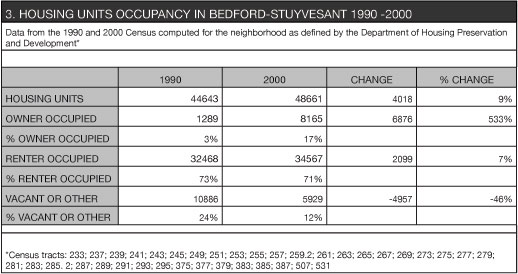

2000 there were 48,661 housing units in total according to the

Department of Housing Preservation and Development. The Department of

Housing has also contributed to stabilize the neighborhood’s low-income

households by building new affordable housing units, many of which are

located on Gates Avenue. All together, the Department of Housing has

rehabilitated or built more than 8000 housing units since 1986. Still

there is room for much more work. According to a 1999 New York survey of

the Department of Housing. Almost 38% of the housing units are on the

same street as buildings with broken or boarded-up windows, the highest

percentage in Brooklyn75. There is still much room for revitalization

and price rise. As most interviewees noted, the architecture of the

neighborhood is its main asset.

|

|

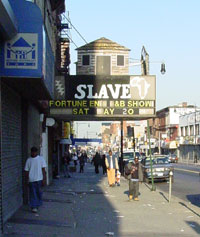

The Slave 1 Theater has been closed to the public for some time.

It only reopens occasionally for weddings and other private

events. Next to it is a fully equipped musical lounge that also

opens sporadically. |

Another asset of the

neighborhood, which might increasingly become an attraction to

newcomers, is the culture of its people. Bed-Stuy might lack economic

capital, but certainly not cultural capital. The many cultures and

lifestyles of Bed-Stuy are, as most interviewees noted, assets to the

community. They connect the neighborhood to the rest of the world and

bring in new ideas. Together with Fort Green, Bed-Stuy is a stronghold

of the Black American culture of New York. From history to

consciousness, the African-American culture developed a critical edge

that is often lacking in the rest of society. Through struggle and

survival, inner-investigation and self-affirmation, reaction and

creation, grew a strong sense of identity. This culture is transnational

by nature. Thanks to its dynamism and fertility it has grown branches

throughout the world. Artists and musicians from the US and the rest of

the world are increasingly looking at Bed-Stuy as a good location to

live. Diego’s story illustrates the crossing realities of the

neighborhood’s past and future.

Originally from Europe, Diego studied jazz at Berklee College in Boston.

After one year in New York he formed a band with players from Boston,

Manhattan, and Brooklyn. The two lead singers, Jahdan and Delie, are

from Bed-Stuy. In need of space for his studio and his family, Diego

decided to move to Bed-Stuy. For the price of a three-bedroom apartment

in Fort Green he was able to rent a duplex in a fully renovated

brownstone with garden on Green Avenue, right by the G train. It took a

few months for Diego and his wife to get used to the neighborhood. The

bohemian utopia has quickly given way to the reality of the ghetto. The

summer they moved in, three people were shot in their block. One of

them, a neighbor known by everyone on the block, was killed by seven

bullets shot by the police because he was supposedly waving a toy gun at

them. A version denied by some witnesses but validated by local

tabloids, which called the victim homeless although he lived with a

woman in a brownstone on the block.76 Despite this, and other incidents,

Diego and his family have integrated the neighborhood well. They know

most of their neighbors and feel at home.

|

|

Noble Society. From left to right: Diego, Jahdan, special guest

Afu-Ra, Rory Jackson, Delie. |

Moving to Bed-Stuy was

strategic for Diego: not only is he getting more space to rehearse and

record with his band, but he is also getting closer to one of his main

sources of inspiration. Many famous black musicians and producers come

from Bed-Stuy, such as Notorious B.I.G. and Spike Lee. Music brought

Diego to Bed-Stuy. He knows that if he makes it in Bed-Stuy, he makes it

in Brooklyn; and if makes it in Brooklyn, he makes it in New York; and

if he makes it in New York? The waves generated by the black culture of

Brooklyn have crossed the oceans to Europe and Asia, and back.

Having grown up in the neighborhood, Jahdan, lead singer in Diego’s

band, doesn’t see Bed-Stuy as any different than any other neighborhood

in Brooklyn. His experience of Bed-Stuy has not changed much in the past

years. With his wife and son, he is part of the 49% of households

earning less than $25,000 a year.77 Recently, Jahdan found a job as a

janitor at a school in Queens. Starting work at 6:30 AM, he wakes up at

4:30 AM every day and earns minimum wage. His wife is unemployed, as one

tenth of the population of the Community District 3.

The Bed-Stuy of today makes it possible for Diego and Jahdan to meet and

create music together. The fusion of the rich local culture and the

motivation of newcomers is explosive. The cultural energy of the

neighborhood lies today in the mix of inspired local and international

artists, creativity, survival, space, informality, instability, change,

potentiality, and openness.

Asked if the neighborhood could be described as “international,” all

interviewees responded affirmatively except Crystal who said that

international was not the first word that would come to her mind to

describe the neighborhood. She sees the neighborhood as rather

homogeneous since the great majority of residents are black. She agreed

however, that the homogeneity of the neighborhood was more “facial” that

cultural, since the black community is very diverse. Jahdan also

observes that African descendents, dispersed around the world, come

together in Bed-Stuy forming an international cultural melting-pot.

According to Delie, Bed-Stuy, with its mix of Afro cultures, is a

breeding ground for contemporary black identity. He says that the street

market of Fulton was a scene where the international black culture of

Bed-Stuy could progress and develop.

None of the interviewees believed that other ethnicities coming in the

neighborhood were a threat to the identity of Bed-Stuy. Delie notes that

five years ago, when he moved in the neighborhood, there were no white

people on his Macon block. Now they are maybe six or seven. Crystal also

observes that there are more white people than in recent memories, but

she believes that the neighborhood will remain predominantly black. The

vast majority of homeowners and buyers are black. Jahdan welcomes the

arrival of other colors. “It had to happen. The interaction of different

people is good for communication and the economy. More white people

moving in means cultural exchange and big money movement.”

Jasper is a twenty-six years-old white American who moved into the

neighborhood about a year ago with three other friends from Switzerland

and Panama. Jasper feels “as comfortable in the neighborhood as a white

guy living in a black neighborhood can feel.” When he first moved in, he

was expecting some reactions from the people. But nobody ever gave him a

negative look. People were neutral. It might be due to the fact that he

is “pretty low-key.” “Some yuppie might be treated differently. It is

probably a matter of attitude.” He notes that the fact that he has been

involved in black-American culture for many years and traveling to

different countries certainly helped him to feel at ease in Bed-Stuy.

Jasper runs a music business specializing in hip-hop, funk, and reggae

records and DJ equipment. He says that if he had only been listening to

mainstream white rock his whole life, it would be different.

CÄline, one of Jasper’s Swiss roommates concurs, “I guess that when you

are real, people feel it.” Because she works in a Non-Governmental

Organization in the United Nation building, she has to be formally

dressed every morning. At first, she was worried about the perception of

other residents. She didn’t want to be seen as a rich white girl taking

advantage of the community. Asked if she considered herself to be

middle-class, she said, “it depends. In terms of income, I am probably

lower class! In terms of education probably middle-class, and in terms

of privileges probably upper-class because I have an excellent insurance

and I can travel.” At first people were wondering what she was doing in

the neighborhood. But any hostility would disappear as soon as they

would hear her French accent. Now she feels she has been completely

accepted. She knows all the shopkeepers, has conversation with everyone

on the block, and guys at the corner call her “Mamy.”

Jasper believes that there is definitively a plateau for white people in

Bed-Stuy. Each time he sees white people he “checks them out,” curious

about what they are doing here. Other white people in the neighborhood

interestingly “threaten your specialty in some ways.” But after giving

it much thought, he came to the conclusion that “diversity is a good

thing; whether it is blacks moving into white neighborhoods or whites

moving into black neighborhood.” However he doesn’t want to see in

Bed-Stuy what happened to many other neighborhoods of New York. “It is a

good thing that there is no more heroin in the East Village, but it is

boring now! White wash completely took over the neighborhood.” ”It is

important to have a good mix.” “Good things can happen because there are

more different types of people.” So what would the right mix be?

“Somewhere between here and Fort Green would be nice.” “The social

atmosphere of Fort Green is nice, but you get a croissant and coffee and

it is five dollars or something! ? They are trying too hard to be like

Manhattan, or some kind of bohemian expensive place.”

Eric is another new resident representative of the ongoing change in

Bed-Stuy. By lack of a better term, Eric could fall into what Richard

Florida calls “the creative class.”78 Eric recently moved with his

boyfriend into a three-story brownstone on Hancock Street. Their

building is occupied by a black writer on the third floor, a white

teacher from Chicago on the second floor, and them, two trendy black

gays on the ground floor. Eric was attracted by the physical character,

space, low rent and excellent transportation that the neighborhood

offers. The A train, five minutes away from his apartment brings him to

his Manhattan office in less than twenty minutes. Because of the

shortage of affordable housing and his lifestyle he had to think

strategically about his living location. Although at first he was much

less enthusiastic about living in Bed-Stuy than his boyfriend, he now

sees the potential of the neighborhood and likes it. Eric believes that,

in five years time, Bed-Stuy will be a new Clinton Hill. That is, a

trendy place to live. It seems that he was always at the right place at

the right time: Chelsea in the early 1990s, Fort Green and Clinton Hill,

in the mid-1990s, and now Bed-Stuy. Recalling when he and his artist

friends moved to Clinton Hill in the mid-1990s, he describes how no

social space existed for them there; they had to make it happen

themselves. Some of his friends opened cafes and shops in Clinton Hill,

which contributed to the transformation of the neighborhood. He would

like to see the same evolution in Bed-Stuy and hopes that new businesses

will open soon, particularly more quality food stores, bars, and

restaurants, offering the goods and services that he needs and replacing

some of the numerous 99 cents stores. He welcomes the arrival of

“educated blacks and brave white people.”

Eric likes the anonymity of cities, but quickly found out that he would

not be a stranger to the people living in his block. Now he begins to

appreciate the strong sense of community of the neighborhood. People

were welcoming, and he did not feel that being a gay couple was more

problematic in Bed-Stuy than anywhere else. He never had problems with

the crackheads at his corner either. Living in Brooklyn he learned to be

“street smart.”

Eric does not see displacement as a big issue in Bed-Stuy now, since

many people own their houses. Anyway, there is nothing he can do about

it, “owners decide the fate of the neighborhood.” “The new replaces the

old, that’s life.” There is still a lot of empty space that can still be

bought out by newcomers.

He doesn’t necessarily see the cultures of newcomers and these of the

locals blending together anytime soon. He says that the people who grew

up in Bed-Stuy are much more complaisant. He doesn’t quite understand

why the people on his block like hanging out on their stoop and doing

barbecue on the street side of their house so much, but he doesn’t

believe that living side by side will be a problem. New shops and stores

will not necessarily be aimed at the present population, he believes,

but integration is not indispensable. “There is enough room for

everybody.”

But is there? In the next section I will analyze the current trends in

housing and describe the kind of pressure exercised by the influx of

middle-class buyers and renters on the long-time residents of the

neighborhood.

Displacement

|

|

Speculation in Bed-Stuy today is reminiscent of the 1920s when

brookers made fortunes turning out properties from white owners

to black owners. In contrast however most home buyers still are

middle-class black people. |

According to Gabriel, of

the Pratt Area Community Council (PACC), displacement is an issue in

Bed-Stuy. His job is to help residents keep their homes. There is not

much he can do for renters, but there are also plenty of brownstone

owners threatened by predatory lenders. Long-time brownstone owners are

under severe pressure to sell because they are often poor but sit on

equities that have hugely appreciated in the past ten years. Bed-Stuy

has the highest number of foreclosures in Brooklyn. Predatory lenders

get foreclosure lists and target owners, offering loans, which they know

the creditor will not be able to reimburse. Erica McHale, homeowner

counselor at PACC and currently dealing with about forty cases, exposes

a typical scenario: A cash poor widow owns a brownstone that her husband

bought thirty years ago for $20,000. She doesn’t have enough liquidity

to renovate the deteriorated roof of her brownstone. A lender knocks at

her door and offers to help. Not only can he provide the funds to

renovate the house, but he can also find people to do the job. He will

give her a $100,000 credit for complete renovation at 12% interest rate

(in some cases it was as much as 19%), and the works can start as soon

as next week. Unaware that her credit history would allow her to get a

much cheaper deal with a conventional lender, and that the loan she

contracted is unaffordable, she trusts the lender, and signs with her

house as a collateral. Very soon, unable to repay her debt, she goes

over foreclosure. The lender gets the house and resells it between

$200,000 and $400,000 (“those in exceptional condition [were] recently

selling for almost $600,000. At of the date of the report, real estate

listings for Bedford-Stuyvesant brownstones were as high as

$750,000”)79, making between 100% and 400% profit.

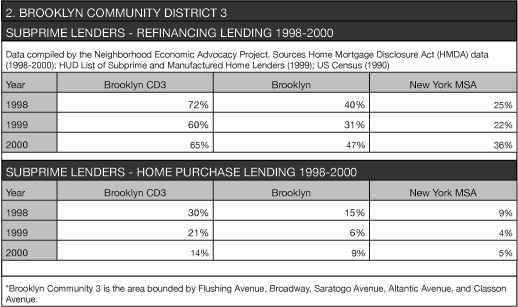

Subprime loans, that is,

loans made by non-conventional lenders are a good indicator of predatory

lending. A study by the Neighborhood Economic Development Advocacy

Project (NEDAP) has shown that the neighborhoods which were historically

redlined by bank (i.e.: non-white ones) are also the one with the

highest concentration of subprime loans:

There is a strong

correlation between concentrations of refinancing loans made by subprime

lenders and neighborhood racial composition. Likewise, there is a clear

relationship between the predominance of subprime loans and high

concentration of foreclosure action filed, by neighborhood.80

Subprime lenders made 30% of home purchase loans in Bed-Stuy in the year

1998, compared to only 9% in New York State. In 2000, Bed-Stuy also had

the highest share of refinancing loans made by subprime lenders in the

city, 65%81. Gabriel points out that the few non-profit organizations

counseling homeowners are overpowered by the dozens of speculators

operating in the neighborhood. Predatory lenders go door to door,

establish personal relationships with homeowners, and obtain deals with

people who could get cheaper loans elsewhere. Not all subprime loans are

predatory, however. They have in the past allowed people living in

redlined neighborhoods to borrow. Today they also serve people with bad

credit history for instance.

Another real-estate scam affecting first-time homebuyers

(disproportionately in communities of color) is preoccupying the PACC:

First time homebuyers are sold dilapidated houses with a home mortgage

loan designed to fail.

Most New York City

property flipping scams involve the same basic elements: real estate

companies buy distressed properties on the cheap and perform cosmetic or

no repairs. These “one-stop shops” then offer a package of services to

borrowers who believe their interests are protected because the loans

are insured by federal FHA insurance a³but instead, appraisals are

inflated to provide huge profits to sellers, loan applications are