|

DVORAK HOUSE

17th Street near Second Avenue

1852-1991

Antonin Dvorak, the Czechoslovak composer, lived with his family in this

nondescript brick row house from 1892 to 1895, during which time he

composed “From the New World,” his most famous symphony. “We live four

minutes from my school in a very pleasant house,” Dvorak wrote to a

friend in Prague shortly after moving to New York. “Mr. Steinway sent me

a piano, free, so we have one good piece of furniture in the parlor. The

rent is $80 a month, a lot for us, but a normal price here.”

In 1991 the Dvorak house was designated a city landmark on historical

and cultural grounds, but the designation was overturned by the City

Council, and the house’s owner, Beth Israel Medical Center, demolished

it to make way for an AIDS hospice.

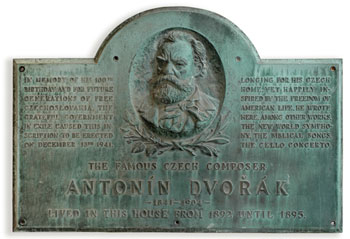

Mounted upon the facade of the house was a handsome bronze plaque. In

the center is a large bas-relief portrait of Dvorak identified in large

letters:

THE FAMOUS CZECH COMPOSER ANTONIN DVORAK

(1841-1904)

LIVED IN THIS HOUSE FROM 1892 UNTIL 1895.

The text in smaller letters, also cast as part of the plaque, reads as

follows:

IN MEMORY OF HIS 100th BIRTHDAY AND FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS OF FREE

CZECHOSLOVAKIANS, THE GRATEFUL GOVERNMENT IN EXILE CAUSED THIS

INSCRIPTION TO BE ERECTED ON DECEMBER 13th 1941. LONGING FOR HIS CZECH

HOME, YET HAPPILY INSPIRED BY THE FREEDOM OF AMERICAN LIFE, HE WROTE

HERE AMONG OTHER WORKS THE NEW WORLD SYMPHONY, BIBLICAL SONGS, THE CELLO

CONCERTO.

On the afternoon of December 13, 1941, only a few days after the sneak

attack on Pearl Harbor, a dedication ceremony was held in the house.

Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia gave the opening remarks:

"... Dvorak produced much that will live forever, and his music will be

played and his name will be honored when the names of Hitler, Mussolini,

and the Mikado [sic] will be found only by referring to the criminal[s]

... of history."

Jan Masaryk, foreign minister of the Czech-Government-in-Exile, then

spoke:

"We Czechoslovakians and Americans of Czechoslovakian descent swear by

the memory of Dvorak that we will do everything in our power to help the

new world, because by so doing we will help to compose the real 'new

world symphony' of free people."

It was Masaryk's father who, with the help of President Wilson, finally

succeeded in establishing Czechoslovakia as an independent nation after

the First World War. Dvorak, and his American house, was for the

Czech-American community and the Czech Government-in-Exile, a precious

symbol of that legacy.

There were three representatives from the New York Philharmonic in

attendance: Bruno Walter, its music director and conductor; Arthur

Judson, who represented the board; and Joseph Kovarik, Dvorak's former

assistant who lived in the house with the Dvorak family forty-nine years

earlier, now a member of the orchestra's viola section. Fritz Kreisler,

the violinist, came to pay his respects. It was Kreisler who renamed

Dvorak's Sonatina for Violin and Piano the "Indian Lament." The

Sonatina, one of Dvorak's "American" works, holds the significant opus

number 100, set aside by the composer for a new work to honor and

entertain his two eldest children, Antonin, age 10, and Otilie, age 15.

The first rendition, in that very room where the dedication ceremony was

held, in Dvorak's own words, "[my] favorite premiere." Dvorak's old

pupils Edward B. Kinney and Harry T. Burleigh (age 75) also attended.

Two youthful Czech-born artists, Rudolf Firkusny, the pianist, and

Jarmila Novotna, the Metropolitan Opera star, performed several of the

"Biblical Songs," also composed in the House. Little did they know that

fifty years later they would become active in the, alas, unsuccessful

campaign to rescue the Dvorak House from the territorial ambitions of

nearby Beth Israel Hospital.

327 East 17th Street, New York City.

Façade of house where the Dvoraks lived from 1892-95

Maurice Peress, American conductor and college professor, described his

1990 visit to the house:

"Not surprisingly, in the hundred years since Dvorak lived there, the

building underwent some modernization, the most radical change being a

circular staircase between parlor floor and the ground floor, and the

removal of the exterior stoop. But the principal rooms, which overlooked

the rear garden and the street, retained their original marble

mantelpieces and much of the woodwork survived as well. The window

shutters were still folded into their paneled boxes, and the massive

doors and window frames were intact.

"I could imagine where Dvorak set the piano that William Steinway sent

over from his 14th Street showroom ... in the back room near the garden

window, with the north light coming over his right shoulder. I

envisioned the Kneisel (string) Quartet during one of their visits, set

up in the corner next to the fireplace, and Dvorak's children gathered

round the piano playing the Sonatina. I wondered, In which room did

Burleigh sing to Dvorak?

"I joined the battle to save the Dvorak House. We gave concerts, formed

a committee of distinguished 'friends' and lobbied local and national

politicians. But within fourteen months of my first visit, the house was

no more. For one brief period our efforts seemed to have been rewarded

when the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission officially

designated the Dvorak House a cultural landmark on February 26, 1991,

but four months later the designation was overturned by the City Council

— the first reversal of its kind by that body. In the interim we

enlisted William Warfield to sing 'Goin' Home' at a City Council public

hearing. The hospital countered, calling upon its deepest political

connections and convincing Isaac Stern, savior of Carnegie Hall, to

declare on television: "We have the music, Dvorak was there for only a

short time, why keep a building that has changed beyond recognition?" To

my naive surprise the New York Times came down against us. An editorial

appeared with the heading 'Dvorak Doesn't Live Here Anymore,' on March

7, 1991. It was an embittering experience, my first real encounter with

city politics and with raw, arrogant power.

"I was heartsick over the destruction of the central icon of Dvorak's

American period, and mortified before my Czech friends who - coming from

a country where historic churches, synagogues, and houses both modest

and grand are cherished and lovingly maintained - could not understand

why the United States would allow such a desecration. I was also

particularly saddened for Jarmila Novotna. Having sung at the dedication

of the plaque fifty years earlier, she was more than another concerned

artist. Novotna was, in the greater sense, a trustee. And knowing that

she had been there with Burleigh, Kovarik, Kreisler, and others who

worked with the master made the hundred years between myself and Dvorak

almost fathomable.

"One of the most devoted Dvorak House proponents, the architect Jan Hird

Pokorny, made arrangements to have the bas-relief plaque and the

parlor–floor mantels removed and placed in storage at the Bohemian

National Hall on Manhattan's East 73rd Street. The building was erected

in 1895/97 by the Czech community with the help of Dvorak, who raised

money for it when he first arrived in New York. These elements have

become part of the Bohemian Hall's planned Dvorak Room. Had the battle

to save the Dvorak House taken place a year later, when the 100th

anniversary of Dvorak's American adventure got underway and a cascade of

Dvorak articles and celebrations descended upon us, I firmly believe the

house would still be standing. Maybe a Dvorak Museum on Stuyvesant

Square park would have had a chance."

Source- http://www.dvoraknyc.org/Dvorak_House_in_New_York.html

|