| New York

Architecture Images- Gone / Demolished / Destroyed New York Tombs |

|

|

architect |

Various |

|

location |

125 White Street |

|

date |

Tombs I, 1838–1902, New York City Halls of Justice and House of

Detention, building by John Haviland Tombs II, 1902–1941, Manhattan House of Detention Tombs III, 1941–1974, Manhattan House of Detention Tombs IV, 1974–present, Manhattan Detention Complex (Bernard B. Kerik Complex 2001-2006) |

|

style |

Various |

|

construction |

stone |

|

type |

Utility |

|

|

"The Tombs" is the colloquial name for the Manhattan Detention Complex, a jail in Lower Manhattan at 125 White Street, as well as the popular name of a series of preceding downtown jails. The nickname has been used for several jails of southern Manhattan. |

| Click thumbnails for larger images- | |

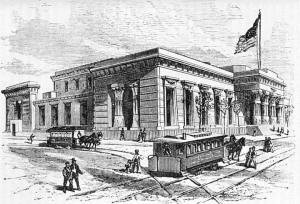

| Tombs I | |

|

|

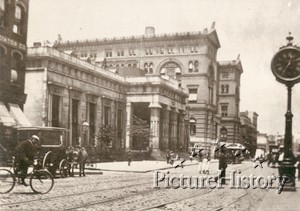

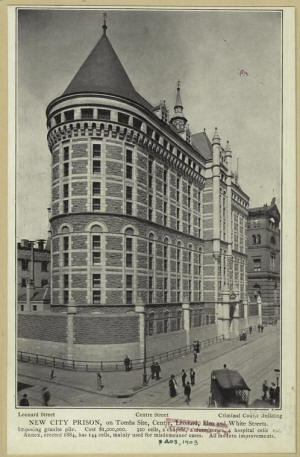

| First Tombs building. View looking north on Centre Street from Leonard Street. 1895 | |

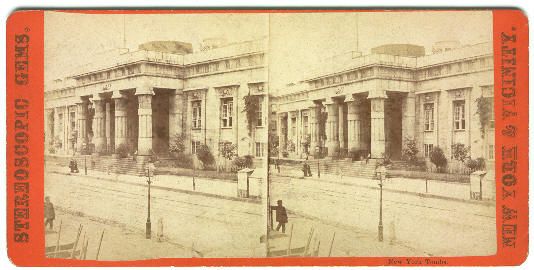

| Tombs I, 1838–1902, New York City Halls of Justice and House of Detention, Egyptian Revival building by John Haviland | |

|

|

| Circa 1870. | |

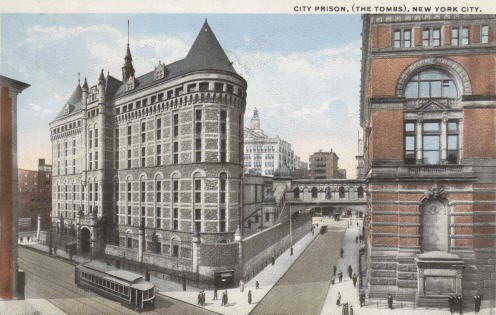

| Tombs II | |

|

|

| The "Bridge of Sighs," connecting the 1902 Tombs prison at left with the 1894 Manhattan Criminal Courts building at right | |

|

|

| Manhattan Criminal Courts building | |

|

|

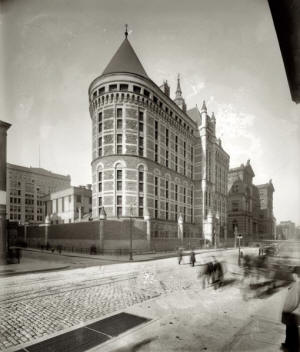

| Tombs II, 1902–1941, Manhattan House of Detention | |

| Tombs III | |

|

|

| Tombs III, 1941–1974, Manhattan House of Detention (photo left c. 1970). Above- the rear gates from the Art Deco building still survive (© 2009 Robert K. Chin.) | |

|

|

|

| Tombs IV | |

|

|

| Tombs IV, 1974–present, Manhattan Detention Complex (Bernard B. Kerik Complex 2001-2006) | |

|

|

|

Manhattan Detention Complex "The Tombs" north tower. 125 White St 28 November 2009 © 2009 Robert K. Chin. |

|

|

The Manhattan House of Detention, known as the Tombs, on White Street in

lower Manhattan, N.Y., is shown in this Oct. 31, 1970 file photo. The first complex to have the nickname was built in 1838. The design, by John Haviland, was based on an engraving of an ancient Egyptian mausoleum. The building was 253 feet, 3 inches in length by 200 feet, 5 inches wide and it occupied a full block, surrounded by Centre, Franklin, Elm (today's Lafayette), and Leonard Streets. It initially accommodated about 300 prisoners. The block on which the building stood had been created in by the filling-in of the Collect Pond, a freshwater pond that had once been the principal water source for colonial New York City. Industrialization and population density by the late 18th century resulted in the severe pollution of the Collect and it was condemned, drained and filled in by 1817. The landfill job was poorly done and in a span of less than ten years the ground began to subside. The resulting swampy, foul-smelling conditions had already resulted in the quick transformation of the neighborhood into a slum known as Five Points by the time construction of the prison started in 1838. The enormous, heavy masonry of Haviland's building was built atop vertical "piles" of gigantic lashed hemlock tree trunks in a bid for stability, but the entire structure began to sink soon after it was opened. This damp foundation was primarily responsible for its bad reputation as being unsanitary during the decades to come. As it also housed the city's courts, police, and detention facilities, The Tombs' more formal title was The New York Halls of Justice and House of Detention. Some regarded it as a notable example of Egyptian Revival architecture in the U.S., but opinion varied greatly concerning its actual merit. "What is this dismal fronted pile of bastard Egyptian, like an enchanter's palace in a melodrama?", asked Charles Dickens in his American Notes of 1842. The prison was well known for its corruption and was the scene of numerous scandals and successful prison escapes during its early history. By 1850, many people were calling for its destruction. By the early 20th century, reforms began to be made as the first prison school for younger inmates in an American adult correction facility was established by the Public Schools Association in 1900. The original building was replaced in 1902 with a new one on the same site connected by a "Bridge of Sighs" to the Criminal Courts Building on the Franklin Street side. That building was replaced in 1941 by one across the street on the east side of Cetre Street with the entrance at 125White Street, officially named the Manhattan House of Detention, though still referred to popularly as "The Tombs". Part of "the Tombs" was eventually closed in 1974 for security and health reasons. Soon thereafter, the structure was demolished and replaced with another building. The current jail comprises two buildings connected by a pedestrian bridge—a 381 bed tower that is the remaining part of the 1941 building at 100 Centre Street (completely remodeled in 1983), and a 500-bed tower north of it, opened in 1990. |

|

|

What served as one of the city's principal jails for more than a half

century was originally named "The Halls of Justice." But the

commonly-used term for the structure was "The Tombs." Even the new

Department of Correction's first official reports in 1896 called it the

Tombs. The massive edifice of granite was built between 1835

and 1840, and took up the square bounded by Centre, Elm, Franklin and

Leonard streets. Its design had been inspired by an ancient mausoleum

that a traveler to Egypt, John I. Stevens of Hoboken, N.J., illustrated

and wrote about in his book "Stevens' Travels." Halls of Justice excavation workers encountered the pond and put down

hemlock logs as a platform on which to build. Five months after it

opened, the building began to sink, warping the cells and causing cracks

in the foundation through which little trickles of water streamed,

forming pools upon the stone flooring. Masons and carpenters were

forever on call, mending, patching, shoring up the structure. The low site's dampness contributed to the building being condemned

by Grand Juries as unhealthy and unfit for its purposes. Originally

designed for about 200 inmates, more than double that were being housed

in it by the 1880s. Two smaller prisons of yellow brick were built in

1885 to relieve overcrowding. Constructed in a kind of rectangular shape, 253 feet long by 200 feet

deep, it appeared from the street only one story in height, the long

windows showing just a few feet above the ground and extending nearly to

the cornice. The main entrance, on Centre street, was reached by a broad

flight of dark stone steps that led to a big and forbidding portico,

supported by four huge Egyptian-like columns. The other three sides

featured projecting entrances and columns. The Tomb's yard Passing through and beyond the ominous entrance, visitors would find

themselves in a large courtyard, at the center of which stood a second

prison. This male prison, 142 feet long by 45 feet deep and containing

150 cells, was entirely separated from the prison for females but was

connected with the outer building by a bridge. The male prison contained a high-ceilinged but narrow hall with four

tiers of cells. The bottom tier opened upon the main floor and each of

the three above it opened upon its own iron gallery, one above the

other. Two keepers were posted on duty in each gallery to guard the

prisoners. The cells, intended for two inmates, often held three. Each tier had its particular purposes. Some ground-floor cells housed

convicts under entence. The second tier was devoted to those charged

with murder, arson, and similar serious crimes. The third tier

accommodated prisoners charged with burglary, grand larceny, and the

like. The fourth tier was assigned to those charged with light offences.

The ground floor cells were the largest, while fourth tier cells were

the smallest. Inmates were assigned cells The Centre street side contained the offices and residence of the

Warden, the Police Court, and the Court of Special Sessions. Over the

Centre street entrance were six comfortable cells. These cells looked

out upon the street and usually held big-time white collar and high

society types. The Police Court opened early every morning. By 10 A.M.

the case calendar was usually completed. The Police Court The Boys' Prison was also located in the Centre street side. The

Women's and Boys' Prisons were serviced by the Sisters of Charity

seeking to minister to the inmates' spiritual wants. One room of the

prison was fitted up as a chapel and religious services regularly held

in it. The week was divided among various religious denominations as

follows: Sunday and Tuesday mornings, Catholics; Sunday and Tuesday

afternoons, Episcopalians; Monday, Methodists, and remaining days for

other denominations. Sisters of Charity A Warden, two Deputy Wardens, and a Matron

supervised Keepers guarding the prisoners. Kitchen work, cleaning chores

and light repair jobs were done by about 30 boy prisoners. Besides the

plain basic food provided by the prison, inmates were permitted to have

provisions purchased for them outside and to receive them from their

family or friends. Changes of clothing also were supplied by their

families. Where families were too poor to make such provision, or where

there were no families, the prison furnished the necessary clothing at

city expense. Prisoners were allowed visits from family and friends.

These were permitted to provide books and other reading matter. The Tombs had a Death Row The Tombs was mainly a prison for detention where persons accused of

crimes were confined until trial and sentence, if any. About 50,000

prisoners were annually confined in it. As soon as they were sentenced,

the convicts were sent to the institutions where they immediately

started serving their terms, except those sentenced to be hanged. These

remained at the Tombs for execution. In 1902 a massive, gray building replaced the Tombs but its chateau-like appearance could not displace in common parlance the name of the original structure whose architectural style had been based on a steel engraving of an Egyptian tomb. Seven decades later that replacement was itself replaced by the present Manhattan Detention Complex but still "The Tombs" name persists. |

|

| Special thanks to- http://www.correctionhistory.org/html/chronicl/nycdoc/html/histry3a.html | |