|

Landmarking Modernist Buildings?

Julia Vitullo-Martin,

March 2005

At its best, the city government's landmarking

process protects the laudable buildings that New Yorkers want saved.

Since being signed into law by Mayor Wagner in 1965, the

Landmarks Preservation Commission  has designated 1,119 individual buildings, 83 historic districts with 11

extensions, encompassing over 23,000 structures in all. Its work has

helped enhance the city's beauty and stabilize many neighborhoods. But

landmarking has its costs. Applied ineptly or too aggressively,

landmarking can halt the transformations and adjustments that are vital

to the city's well-being. Every single landmark ruling is fraught with

thorny issues and potential harm. Which buildings are truly worth

protecting? Which ones are so handsome, historic, or innovative that the

awesome power of the government should be invoked to prevent their

demolition—or even halt any major change in structure and use? Which are

so significant that they should be permanently consigned to the LPC's

under-funded and ponderous regulatory oversight?

has designated 1,119 individual buildings, 83 historic districts with 11

extensions, encompassing over 23,000 structures in all. Its work has

helped enhance the city's beauty and stabilize many neighborhoods. But

landmarking has its costs. Applied ineptly or too aggressively,

landmarking can halt the transformations and adjustments that are vital

to the city's well-being. Every single landmark ruling is fraught with

thorny issues and potential harm. Which buildings are truly worth

protecting? Which ones are so handsome, historic, or innovative that the

awesome power of the government should be invoked to prevent their

demolition—or even halt any major change in structure and use? Which are

so significant that they should be permanently consigned to the LPC's

under-funded and ponderous regulatory oversight?

Because buildings become eligible for designation

at 30 years of age, many modernist and post-modernist buildings are

being pushed onto the docket for preservation. But these buildings bring

new issues to bear. For one thing, they are often unloved.  Unlike the traditional 19th- and early 20th century masonry buildings

they routinely replaced, the severe glass-and-steel modernist towers are

often ugly, impersonal, and out of place in their neighborhoods. In

modernist eyes, innovation was always to be preferred to orthodoxy.

Utilitarianism was the goal and the creed. At its most fundamental, the

aesthetic of modernism defied and debased the old. The modernist

building was meant to stand out, not to fit in, to break the street

wall, not to follow it. The shearing of the urban fabric was modernism's

intent—not a mere byproduct. Modernist architects prided themselves on

being mavericks, revolutionaries, men above the crowd. They were, in

historian Vincent Scully's phrase, hero architects.

Unlike the traditional 19th- and early 20th century masonry buildings

they routinely replaced, the severe glass-and-steel modernist towers are

often ugly, impersonal, and out of place in their neighborhoods. In

modernist eyes, innovation was always to be preferred to orthodoxy.

Utilitarianism was the goal and the creed. At its most fundamental, the

aesthetic of modernism defied and debased the old. The modernist

building was meant to stand out, not to fit in, to break the street

wall, not to follow it. The shearing of the urban fabric was modernism's

intent—not a mere byproduct. Modernist architects prided themselves on

being mavericks, revolutionaries, men above the crowd. They were, in

historian Vincent Scully's phrase, hero architects.

And they built buildings that were not meant to

last. The lifespans of modernist buildings are often short because their

architects used unproven materials rather than those tested by time.

Preserving them involves correcting the natural obsolescence that

inevitably occurs with the passage of time but also refurbishing all or

most of the materials as well—at enormous expense.

CITY-DESTROYING CRITERIA

Since the very idea of preservation was inimical to the modernists,

today's preservationists must simply ignore the many paradoxes and

contradictions inherent in the arguments they're making for landmarking

mid- and late-20th century buildings. With no irony intended, today's

preservationists actually cite as criteria for preservation the

implementation of the city-destroying devices that earlier preservations

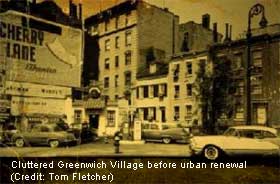

had rightly decried. Take the superblock, invented by modernists as a

device for eliminating the clutter and mess of city streets, allowing

clean, dominant, uniform towers to be built where a jumble of mixed-use

buildings had once stood.  The superblock erased New York's tight street grid, famously maligned by

writer Lewis Mumford as the soulless invention of commercial capitalism,

a pernicious device for dividing land into salable parcels. But today we

recognize that Mumford was utterly wrong. Do we not all agree with Jane

Jacobs that the urbane mixtures of buildings of varying age,

condition—inevitably swept away by the superblock—are a necessary

condition of thriving urban life? That whenever possible, the superblock

should be broken up into short, pedestrian-friendly blocks, much as New

York had been laid out in the 19th century?

Nonetheless, the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation,

ordinarily a ferocious advocate for the Village's pre-World War II

heritage, recently urged the landmarking of I. M. Pei's University

Village/Silver Towers development by saying it serves as "an exceptional

example of thoughtful and urbane ! post-war superblock urban renewal

schemes."

The superblock erased New York's tight street grid, famously maligned by

writer Lewis Mumford as the soulless invention of commercial capitalism,

a pernicious device for dividing land into salable parcels. But today we

recognize that Mumford was utterly wrong. Do we not all agree with Jane

Jacobs that the urbane mixtures of buildings of varying age,

condition—inevitably swept away by the superblock—are a necessary

condition of thriving urban life? That whenever possible, the superblock

should be broken up into short, pedestrian-friendly blocks, much as New

York had been laid out in the 19th century?

Nonetheless, the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation,

ordinarily a ferocious advocate for the Village's pre-World War II

heritage, recently urged the landmarking of I. M. Pei's University

Village/Silver Towers development by saying it serves as "an exceptional

example of thoughtful and urbane ! post-war superblock urban renewal

schemes."

Similarly, many preservationists are arguing that

the historical era of modernism—whatever its substantive merits—should

be saved for its own sake. Thus they are urging the landmarking of

architect John Portman's immense, brutal, street-defying Marriott

Marquis Hotel in Times Square, built on the site of the

Helen Hayes Theatre, which had been widely regarded as the loveliest

theater in New York, until it was demolished in 1982 to build the hotel.

Vickie Weiner, a preservationist who headed up the

Municipal Art Society's 30 Under 30  watch list to alert the public to vulnerable modernist buildings, says

that many young architects admire Portman's work. She adds, "How do you

raise consciousness? Some of our jury members felt that in time we would

have a new appreciation for the building. The battle over the Helen

Hayes spurred the LPC to designate the remaining theaters. This building

is a benchmark for remembering that this really did happen. Is there a

value to retaining the historical evidence of an important event?"

Or as architect (and 30 Under 30 juror) Paul Byard told the New York

Sun, "Sure, we don't like the building, but the building of the Marriott

Marquis represents a pivotal historical decision in developing the West

Side."

watch list to alert the public to vulnerable modernist buildings, says

that many young architects admire Portman's work. She adds, "How do you

raise consciousness? Some of our jury members felt that in time we would

have a new appreciation for the building. The battle over the Helen

Hayes spurred the LPC to designate the remaining theaters. This building

is a benchmark for remembering that this really did happen. Is there a

value to retaining the historical evidence of an important event?"

Or as architect (and 30 Under 30 juror) Paul Byard told the New York

Sun, "Sure, we don't like the building, but the building of the Marriott

Marquis represents a pivotal historical decision in developing the West

Side."

Important as it is to remember and reflect on

destructive events in the city's past, this is no time to set up new

criteria for landmarking. We should judge modernist buildings the same

way we judge all buildings: Do they have merit in and of themselves? Are

they good buildings? Are they good neighbors? Are they or can they be

made economically viable? Do they make the city a better place? Further,

to the life of a neighborhood, it matters nothing that a bad building—or

worse, a huge development—was designed by an eminent architect.

Designation is, as Vickie Weiner notes, a blunt instrument. But

designation also involves an immensely important tool for public

discussion: hearings. Let's hear what the public has to say. The city's

uniform land use review process, ULURP, has taught everyone the

usefulness of public education and debate—a lesson that should not be

lost on the LPC. It would also be useful for the LPC to adopt a rigid

ULURP-like timetable! so that all parties understand that a decision

will be made or forfeited by a predictable date.

In deciding to champion the landmarking of

modernist buildings, New York preservationists are playing a dangerous

game, in effect proposing to prevent the city's fabric from mending

itself. The damage done the urban fabric by modernists can be un-done,

if neighborhoods are allowed to heal naturally over time.

Preservationists should be the last people to stand in the way.

WHAT’S NEXT

With an annual operating budget around $3.5

million, the LPC is both under-funded and under-staffed for the amount

of work it is expected to handle. In 2003, it designated 12 individual

buildings and 3 historic districts as landmarks. Preservationists are

suing the LPC over its refusal to hold public hearings on the planned

reconstruction of Edward Durrell Stone's 2 Columbus Circle, which the

LPC had decided was undeserving of landmarking in 1996. The building's

new owner, the Museum of Arts & Design, intends to  demolish the unusual marble-clad facade—which prompted architecture

critic Ada Louise Huxtable to call it the "lollipop building"—in late

May.

Preservationists are also urging the LPC to hold hearings on proposals

to demolish two movie theaters on Manhattan's Upper East Side—Cinemas 1,

2, and 3, on Third Avenue, built in 1962, and the Beekman, on Second

Avenue, built in 1952. Are these buildings worthy of permanent

designation? Is the Grace Building on West 57th Street of merit, as 30

Under 30 suggested? or One Chase Manhattan Plaza at Pine and Liberty, as

the architect Robert A. M. Stern proposed? The outcome of this debate

will set the parameters for the city's future.

demolish the unusual marble-clad facade—which prompted architecture

critic Ada Louise Huxtable to call it the "lollipop building"—in late

May.

Preservationists are also urging the LPC to hold hearings on proposals

to demolish two movie theaters on Manhattan's Upper East Side—Cinemas 1,

2, and 3, on Third Avenue, built in 1962, and the Beekman, on Second

Avenue, built in 1952. Are these buildings worthy of permanent

designation? Is the Grace Building on West 57th Street of merit, as 30

Under 30 suggested? or One Chase Manhattan Plaza at Pine and Liberty, as

the architect Robert A. M. Stern proposed? The outcome of this debate

will set the parameters for the city's future.

|

|