|

New York

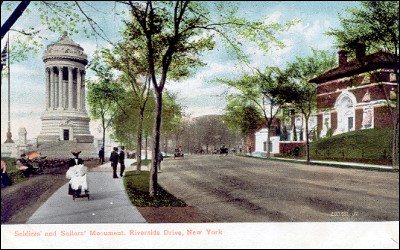

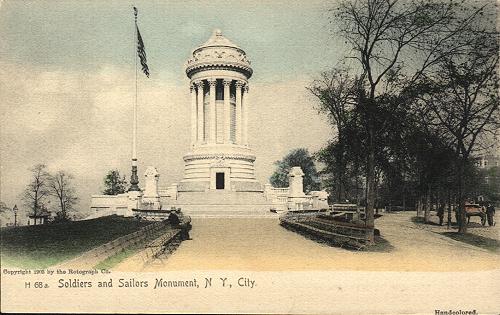

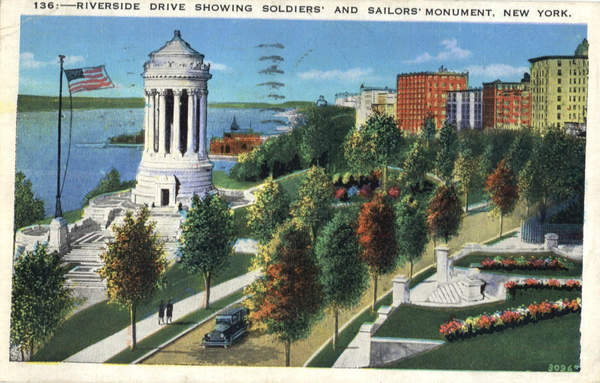

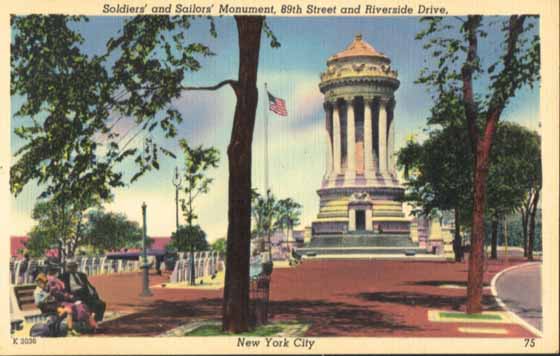

Architecture Images-Harlem and the Heights Soldiers and Sailors' Monument |

|

architect |

Charles and Arthur Stoughton |

|

location |

Riverside Drive at 89th Street |

|

date |

1902 |

|

style |

Neoclassical |

|

construction |

marble and granite |

|

type |

Monument |

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

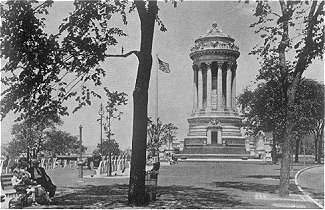

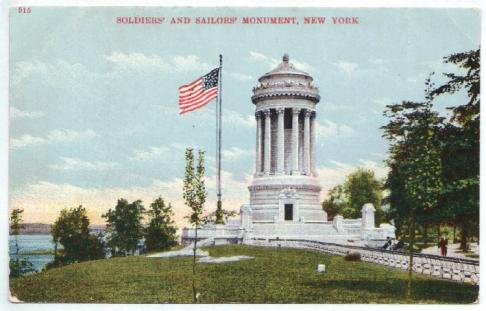

This massive circular

temple-like monument located along Riverside Drive at 89th Street

commemorates Union Army soldiers and sailors who served in the Civil

War. This monument, one of the few in a city park that the New York

Landmark Commission designated a landmark, was designed by architects

Charles (1860–1944) and Arthur Stoughton (1867–1955), who won a

competition with this ancient Greek design.

The marble monument, with its pyramidal roof and 12 Corinthian columns, is based on the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens. It was commissioned by the State of New York, and dedicated on Memorial Day in 1902. Sculptor Paul E. Duboy carved the ornamental features on the monument. The pillars list the New York volunteer regiments that served during the battle as well as Union generals and the battles in which they led troops. For years the monument was the terminus of New York City’s annual Memorial Day parade. In 1961 the City spent more than $1 million to fix the monument’s marble façade, which had deteriorated, and portions of the monument were replaced with more durable granite. |

|

|

Streetscapes/Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument,

at 89th Street and Riverside Drive;

A 1902 Memorial to the Fallen of the Civil War By CHRISTOPHER GRAY Published: October 13, 2002, Sunday IT took nearly a decade to build the white marble Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument, at 89th Street and Riverside Drive. Locations had been suggested all over Manhattan by those eager to have the monument in their neighborhoods -- and by those who weren't. Earlier this year an anonymous donor suggested expanding the monument's formal plaza farther south, replacing old blacktop and benches. The Parks Department liked the idea, but after objections from the New York City Art Commission, the donor withdrew his offer, and the department now says that the proposal will have to wait. New York had no serious plans for a Civil War memorial until 1893, when a Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument Association was formed. It proposed a triumphal arch at Grand Army Plaza, at 59th Street and Fifth Avenue, one of New York's most prominent open spaces. But the Grand Army Plaza site was opposed by the Federation of Fine Arts, an organization representing most of the art groups in the city. It said that the monument would be dwarfed by the growing collection of tall hotels there and proposed instead 72nd Street and Riverside Drive. More parochial interests soon came into play. East Side interests vied to have the monument at Grand Army Plaza, while a group of West Siders, eager for the Riverside Drive site, said that the plaza site was unbuildable and that water would be struck in excavating for the foundations. More than 20 meetings were held in 1896 and 1897 to try to choose a site, and other solutions were proposed, among them the triangle between 22nd and 23rd Streets and Broadway and Fifth Avenue. Naval officers did not like the Grand Army Plaza idea because it was not within sight of water, a matter of little importance to Army veterans, who preferred the Fifth Avenue location. The Monument Association still sought the Fifth Avenue location, while the newly established Art Commission, created to review the design of works of art built on public land, opposed it. The Art Commission finally ruled decisively against the site in 1897, and Sherman Square, Abingdon Square, Union Square, the Battery and the northeast corner of Central Park were all proposed. Things finally seemed to be moving in 1899 when the Monument Association and the Department of Parks agreed to a site for the memorial atop Mount Tom, a round, rocky outcrop in Riverside Park near 83rd Street. But then developers erected several apartment houses near the corner, an act that The New York Times said would give the monument ''an insignificant appearance.'' There was also a protest against building on top of a natural feature. In late 1899 the Monument Association agreed to relocate the memorial farther north, to a modest plateau at 89th Street and Riverside Drive. The architects Stoughton & Stoughton designed a great drum surrounded by 12 Corinthian columns, set on a complex series of plazas connected by terraces and walkways. The last obstacle was Elizabeth Clark, owner of the Dakota at 72nd Street and Central Park West and other West Side properties, who was building a grand Beaux-Arts-style mansion at the northeast corner of 89th and Riverside. In 1900, Mrs. Clark -- the widowed daughter-in-law of Edward Clark, the Dakota's builder -- got a temporary injunction against the monument, claiming in court papers that it would ''interfere with the flow of light and air and obstruct the view'' and that it was ''unsightly and inartistic.'' She lost the case in mid-1900, and work went ahead. At that time the plans called for a grand staircase descending to a water gate on the Hudson and, south of the flagpole plaza at 89th Street, a long approach with a battlemented retaining wall along the park. It was not until Memorial Day in 1902 that the $250,000 monument was dedicated. Mrs. Clark, the former opponent, patriotically decorated her house with flags and bunting. Mayor Seth Low said at the ceremony, ''The memories that hover around it already clothe it with a light that makes it sacred to the eye.'' The stairway to the river was not built, nor was the battlemented wall to the south. Photographs of the period are not completely clear, but it appears that the area south of the plaza was simply paved, or perhaps treated with pebbles. PERIOD accounts indicate that the heavily sculptured bronze door at the base of the monument, now kept locked, was open to visitors. The interior was completely finished, with white marble walls and a mosaic floor underneath a dome. The biggest change to the monument took place in the 1930's, when the plaza's yellow brick, which contrasted so well with the white marble trim, was replaced with the orange-colored stone common to Parks Department projects of the period. The monument is one of New York's best works of the turn-of-the-20th-century City Beautiful movement. But it is marred by the scruffy appearance of the area just south of the stone plaza, which looks as if it might be the parking lot of a factory abandoned years ago. The binder of the plain black asphalt -- which apparently replaced the original paving -- has come out, leaving the approach to the monument an irregular, undulating surface of black gravel, relieved by occasional tree stumps and benches, a fitting complement to the line of parked cars along Riverside Drive that crowd the monument on the east. Earlier this year the Parks Department, backed by the offer from the anonymous donor, began to seek approvals for rebuilding the plaza at the south. Adrian Benepe, the department's commissioner, said that it had proposed ''a modern interpretation of a formal design,'' replacing the deteriorated asphalt with granite pavers in a pattern echoing the 1902 plaza. The Landmarks Preservation Commission approved the proposal with some modifications. But Landmark West, a neighborhood preservation group, opposed the design. ''The design blurs the intentional, sharp distinction between the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument and its historically naturalistic setting in Riverside Park,'' said Kate Wood, the executive director. She said that the expansion of the plaza in formal materials and design would dilute the character of the monument itself. Her group favors the softer, less formal treatment of 1902, although it appears that that choice may have been made purely for economic reasons. The Art Commission also objected to the design. Lark Anton, a commission spokeswoman, declined to give the agency's reasons. Although a revised proposal might have been approved, Mr. Benepe said that the donor withdrew his offer in part because of frustration with the criticism. ''It was a vigorous debate, and many valid opinions were expressed,'' Mr. Benepe said. ''We believe that our design was just as valid.'' If another donor comes forward, there is still plenty to do at the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument. Many of the structure's joints are wide open, and some of the stone flags of the 1902 plaza are displaced because of erosion underneath. One long slab of marble is tipped up and broken in half. The many coatings of anti-graffiti paint are perhaps unavoidable, but the ornamental bronze doorway has been damaged by vandals. At some point the richly sculptured bronze flagpole base, which featured ship forms, wreaths and other elements, was removed, and much of the 1930's orange-colored stone is chipped and splitting. Two large plazas, one at the north end, the other to the south, are closed off with metal fences and chains. Parks officials say they have been temporarily fenced off to discourage certain antisocial activities, but decline to be more specific. Mr. Benepe said that no major work is scheduled for the structure, but that in the next few years the department will have it surveyed. He added that he is still seeking a generous New Yorker to pay for the rehabilitation of the plaza to the south, with a different design. ''I don't consider the case closed,'' he said. Published: 10 - 13 - 2002 , Late Edition - Final , Section 11 , Column 1 , Page 7 Copyright New York Times. |

|

|

links |

|